Schlock and Awe

ON OCTOBER 7, the Nova Exhibition opens in Berlin’s former Tempelhof Airport. Over the next six weeks, visitors can enter the immersive memorial, which is intended to pay tribute to the 378 victims who were murdered by Hamas in the attacks of October 7 at the Nova music festival. “The events on that black Saturday,” the exhibition website reads, “will be presented as a shocking contrast between light and darkness, good and evil, that is relevant to the entire world.”

The Nova Exhibition opened in Tel Aviv in December of 2023 and has since traveled internationally, with stops in New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, Washington DC, Miami, and Buenos Aires. The exhibition, which varies slightly from location to location, incorporates multimedia components, including film footage and audio, as well as both real artifacts and recreations of objects from the site, designed to give visitors a visceral and tactile experience of the day. The exhibition was initiated by the founders of the Nova music festival along with entertainment entrepreneurs, and put out in collaboration with Breeze Creative, an interactive design company whose clients include the Miami Children’s Museum, the Land of Legends theme park in Turkey, and Elbit Systems, an Israeli defense contractor, among others.

To make sense of the exhibition, as well as some of the questions it poses as it arrives in Germany, I spoke to Ben Ratskoff, assistant professor in the Critical Theory & Social Justice department at Occidental College in Los Angeles and member of the Diasporist’s advisory board. In September, Ratskoff published “Prosthetic Trauma at the Nova Exhibition: Holocaust Memory, Reenactment, and the Affective Reproduction of Genocidal Nightmares” in the Journal of Genocide Research, which draws upon his visits to both the Los Angeles and the New York installations. His article is a significant close reading of the exhibition, as well as an fascinating exploration of broader trends in Holocaust memorialization and museum practices.

Two years since the attacks of October 7, Israel’s ongoing offensive in Gaza has claimed the lives of more than 67,000 Palestinians. As Ratskoff argues in his paper, the framing of the exhibition blurs memorialization with atrocity propaganda, obscuring context and reinforcing the claustrophobic trauma of the events of the day. As a result, the exhibition’s arrival in Tempelhof — a striking choice, given the airport’s iconic Nazi architecture — is bound to be met with special scrutiny. Although tickets come at a price of 20 EUR each, Berlin’s government is paying nearly 1.4 million EUR for the exhibition (at a time in which the effects of severe budget cuts are still rippling through the city’s cultural sector).

When tipBerlin, the owners of the English-language local outlet The Berliner, accepted an advertising partnership with the Nova Exhibition, contributors, who felt the partnership established an editorial stance they had not consented to, threatened to withhold their labor should the magazine go ahead. For now, visitors can attend the exhibition (and purchase a 90 EUR limited edition t-shirt, among other merchandise) and the Berliner’s freelance staff is on strike.

– Julia Bosson

Julia Bosson: You recently wrote about the Nova Exhibition in an article published in the Journal of Genocide Research. Could you walk us through the exhibition? What is the visitor experience?

Ben Ratskoff: The Nova Exhibition is a mobile memorial that seeks to commemorate victims of the October 7 massacre at the Nova outdoor music festival near Re’im in the Gaza envelope. In doing so, it draws upon immersive, multimedia theatrics that we associate more with a theme park, and in particular with what is called a “dark ride” — rides like Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion or it’s a small world where visitors are guided through tightly controlled and intensely staged enclosed spaces. Immersion is of course not unique to the Nova Exhibition; it’s symptomatic of contemporary museum practices in general, including memorial museums.

Before entering the exhibition, a large placard provides visitors with some minimal context but mostly a highly Manichean, melodramatic, and depoliticizing narrative: “Thousands of radiant souls came together for a celebration of unconditional love and the spreading of light. In one moment, the festive atmosphere is shattered. The Angel of Death swoops, firing a barrage of hateful missiles that cut through the joy like an icy winter wind.” The victims are dissolved into pure equivalence and the perpetrators masked behind an evil principle.

Suddenly, coinciding with sunrise, the music shifts from symphonic climax to trance music, facilitating the visitor’s affective shift from a spectator-witness to surrogate festival-goer.

The beginning of the exhibition itself mirrors the structure of a pre-ride storytelling sequence establishing the setting, the characters, and the inciting incident of the ride’s world. In this case, visitors watch a video about the festival itself, which celebrates trance music as the universal heartbeat of humanity, for example, and shows video footage of the festivalgoers in euphoric slow-motion. Suddenly, coinciding with sunrise, the music shifts from symphonic climax to trance music, facilitating the visitor’s affective shift from a spectator-witness to surrogate festival-goer. Then, visitors are invited to proceed onward.

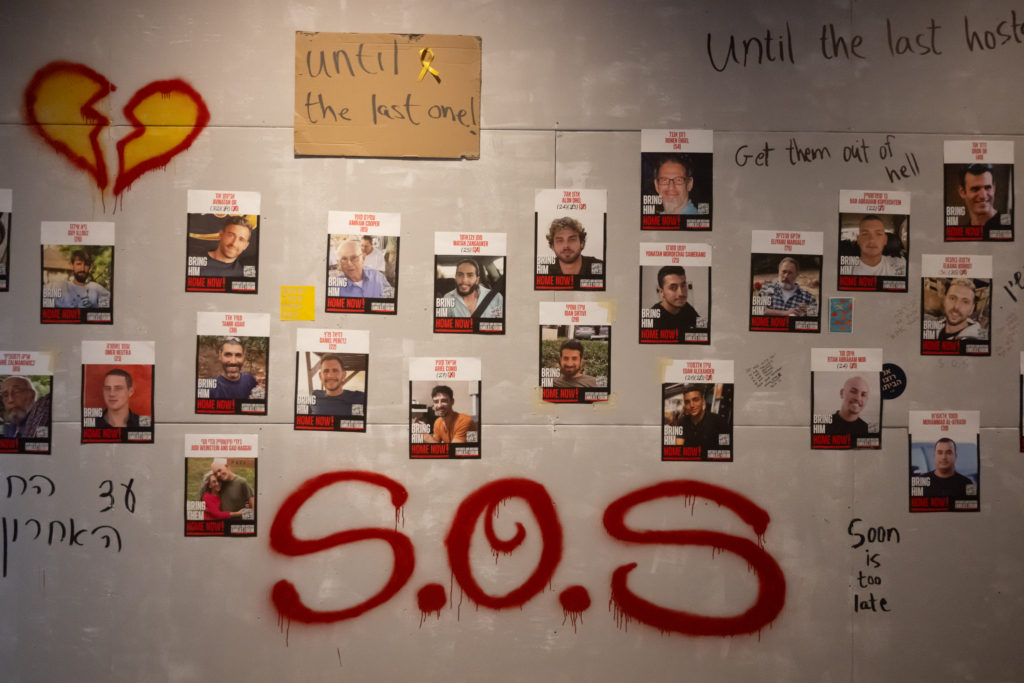

Visitors then enter a dark room that is supposed to simulate the festival campgrounds. It’s similar to walking through a haunted house: visitors move in packs in an enclosed space with low ceilings along a relatively controlled circulation path, looking from side to side at the life-size installations. And there is a cacophony of screams, coming from the large screens covering the walls and playing anonymized atrocity footage from the perspectives of both the perpetrators and the victims, with no curatorial explanations, identifications, or framing. The video screens surround dioramas of objects and artifacts collected from the festival campgrounds, functioning as relics. Sleeping bags, water bottles, tents, wrappers… A placard at the entry emphasizes that all of the objects are “authentic” and asks visitors to “please, touch them,” which results in a tactile personalization of the immersive experience as well as a fetishistic sense of live traumatic transmission. This room is where the exhibition most intensely invites visitors to participate affectively and imaginatively in immersive theatrics as a kind of vicarious victimhood.

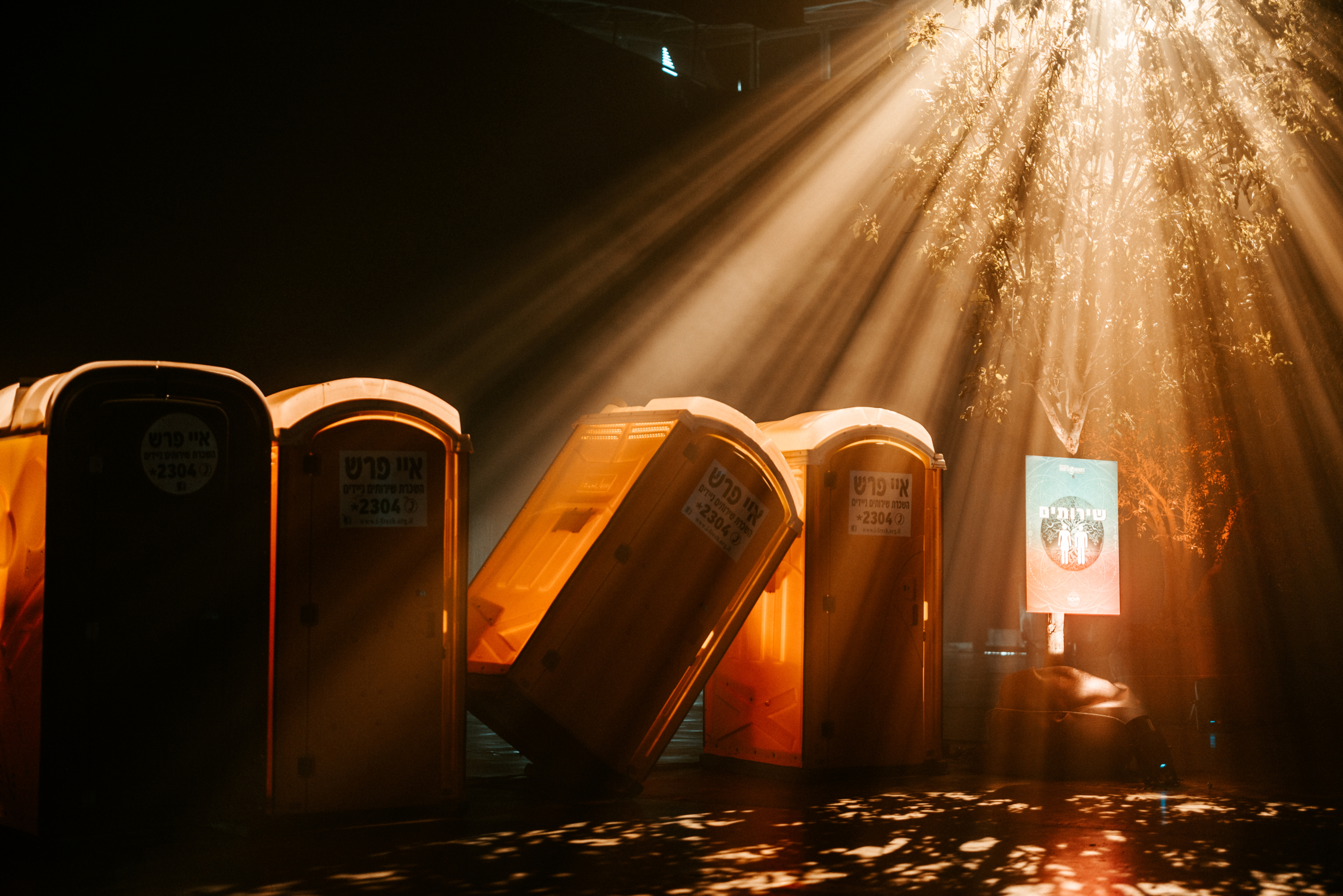

Finally, visitors enter a huge room with both recreated and salvaged objects, like portable toilets with bullet holes in them, burnt-out cars, a recreation of the bar at the festival with all the bottles out, in media res, as if they were just left there. And then there is the table of victims’ shoes, which is obviously a reference to Holocaust museology.

JB: I’m interested in how the exhibition positions visitors both as spectators as well as stand-ins for the victims, creating that sense of traumatic transmission, as you put it. What are the effects of that?

BR: This is something that the Nova Exhibition certainly did not invent. It follows what Pascale R. Bos has called a “Holocaust pedagogy of identification,” which facilitates affective identification with victims often through forms of simulation and role-playing. At the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington DC, for example, visitors are given an identity card of a victim to carry with them; at the end, visitors find out if they lived or died. And of course there is the actual simulation portion of the permanent exhibit, in which visitors pass through a cattle car, under a replica of the Arbeit Macht Frei sign from Auschwitz, and then into a recreated prisoner barracks, all of which create an approximated sense of having been there.

But at what point does it just obliterate the distance between visitors and victims and appropriate their suffering for the visitor’s own consumption?

The point is to cultivate empathy. But at what point does it just obliterate the distance between visitors and victims and appropriate their suffering for the visitor’s own consumption? At the end of the day, the visitor leaves the museum whole and intact, a privilege the actual victims of course did not have. And so, the visit becomes a thrilling experience, similar to a haunted house or a horror film.

In terms of the Nova Exhibition, this affective identification with the victims of the October 7 attacks also blocks out reflection on the causes and consequences of the day. In a context like the United States, which is geographically quite removed from Israel-Palestine, it can amplify narratives of Jewish insecurity that have been used to justify a whole range of repressive policies. This happened in two ways: firstly, while the exhibition is open to the general public, Jews were specifically targeted as visitors through institutional channels like the Jewish Federation, which advertised the exhibition and sometimes even arranged cross-country trips to visit the exhibition, and through on-campus Jewish organizations and networks — essentially inviting Jews to a surrogate experience of antisemitic victimization. On the other hand, there’s a secondary appropriation by local political elites who use the site as a platform to amplify narratives of insecurity and exploit them for their own repressive agendas.

As the exhibition moves to Europe, there are different issues. Holocaust pedagogy and memorialization in Western Europe has often resisted identification with victims, which would seem inappropriate. And because the Jewish population is much smaller than in the US, we can assume that the primary public targeted to visit won’t necessarily be a Jewish one. In Germany, in particular, there is the specific post-perpetrator context that raises questions about what it means to identify with and as Jewish victims. And these questions are amplified by the very site chosen for the Nova Exhibition in Berlin, the Tempelhof airport terminal — itself a relic of Nazi monumentalism. I mean, it’s sort of literally a haunted house.

JB: When we think about what it means for the exhibition to arrive in Germany, my instinct is to connect that to a larger trend of projected over-identification with the victims of the Nazis out of a misguided sense of historical responsibility or a perversion of Staatsräson. We hear over and over again Germans offering personal expressions of pain over antisemitism, even if the antisemitism in question is a peaceful pro-Palestine demonstration.

BR: When Jews in the United States appropriate the exhibition’s experience of victimization for themselves, there’s a problem of collapsing the real distance between their own lives and the conditions that they live in with those who were victimized on October 7. In the context of Germany, the problem of appropriation becomes ethically fraught as non-Jewish Germans — the beneficiaries of Nazism and the Holocaust — can, through experiencing the exhibition, in fact imagine themselves as a Jewish victim. In this way, they can shed the burden of post-perpetrator responsibility and claim the moral privileges of victimhood — without actually having to experience violence or suffering, of course. And by occupying the position of Jewish victims, by “communing with Jewish suffering” (a term I borrow from Adam Sutcliffe), they can make accusations of antisemitism against others.

Despite the histrionics about “Holocaust relativization” in Germany, the projection of the memory of Nazism onto Palestinian Muslims is permissible because it converges with widespread anti-migrant xenophobia and policy.

In this context, it works perfectly for a certain part of German society, for whom the so-called “new Nazis” are Palestinian Muslims. Despite the histrionics about “Holocaust relativization” in Germany, the projection of the memory of Nazism onto Palestinian Muslims is permissible because it converges with widespread anti-migrant xenophobia and policy. White Germans can rehabilitate an exclusionary nationalism while aligning themselves with Jewish victimhood — a remarkable, if grotesque, achievement. When I was in Berlin this past May, I saw a poster for a party/fundraiser at About:Blank that had the Nova logo and was called “We Will Dance Again.” Who is this we in Germany? It’s an imagined collectivity under threat from antisemitic barbarians. And it’s incredible to include the German public inside of it.

In May of 2024, Platz der Hamas Geiseln was set up in Bebelplatz in Berlin, which had a reconstruction of what they called a “Hamas tunnel.” Visitors could walk through imagining they were simulating the suffering of Israeli hostages. Of course, again, it’s essential to emphasize that visitors would not in fact experience what the hostages were and are experiencing, but that they would think they were approximating it. When it opened, I heard that students at Jewish schools were specifically invited to visit. What does it mean for non-Jewish Germans to invite Jewish children to a simulation of what the former thinks of as antisemitic terror? This goes beyond voyeurism — there’s a certain kind of sadism there.

JB: That connects to something you’ve been writing about, a theory of “hyperreal antisemitism,” which is relevant here and closely linked to the “pogrom” in Amsterdam in November of 2024. Could you tell us a little bit about what hyperreal antisemitism is and how an exhibition like this feeds into it?

BR: Among those who detected the construction of a moral panic in the days and weeks after October 7, there was a tendency to dismiss the language of Jewish fear and Jewish insecurity as mere ideological falsehood. But when I spoke to some Jewish undergraduate students, some of them my own, there was an immediacy to their expressions. They were feeling things that were overwhelming for them. In the absence of threats to their physical safety on campus, I needed to understand what was cultivating and giving language to that feeling.

That’s partly what shaped my interest in the Nova Exhibition as an apparatus that cultivates, intensifies, and narrativizes certain forms of affect. It led me to consider the effect that public discourses alerting to acute and rising threats of antisemitism — and the framing of certain events not simply as antisemitic but as live reenactments of Nazism and the Holocaust — could actually be having on the public, both Jewish and non-Jewish. We know from criminology scholarship in general that anxiety about crime is not equivalent to actual rates of victimization.

I felt that theories of hyperreality were useful in thinking about this blurring between the real and the imaginary in anti-antisemitic discourse, especially because this discourse was so dependent on a particular canon of signs, symbols, and icons. All of this became even more clear in November 2024 when street violence between Israeli football hooligans and locals in Amsterdam was rapidly narrativized by senior politicians as an unfolding “pogrom.” I turned to theories of hyperreality to clarify how certain fantasies of anti-Jewish violence were circulated in political discourse and were fabricating real emotions. Hyperreality describes how signs, symbols, and icons no longer seek to imitate reality but aim to simulate and substitute for it, generating the real from models. Critically, Jean Baudrillard draws on the classic Littré French dictionary to explain: whoever fakes an illness can simply stay in bed and make everyone believe he is ill, but whoever simulates an illness produces in himself some of the symptoms. What is key here is that hyperreality is not about pretending. A pogrom did not take place, to paraphrase Baudrillard, but the effects of this narrative simulation were very real. Theories of hyperreality help us understand what it means to simulate antisemitism through public discourses that blur the real and the imaginary, and thereby actually produce symptoms such as fear.

JB: If these feelings are real, then fear is a real thing that has to actually be grappled with and dealt with. I’m curious about the way in which hyperreal antisemitism might actually produce real antisemitism, both in terms of how it positions Jews as helpless victims, and in how it can obscure real instances of antisemitism.

BR: That’s basically one of the problems, I think. Part of the power and allure of the hyperreal is that it makes it almost impossible to distinguish. I think it may reflect an imbalance between the emotional impact of antisemitism today, in all of its complexity, and that of terms such as “pogrom” and “Nazi.” which are what Sara Ahmed calls “sticky” signs, having accumulated affective value through their overcirculation. To be clear, this is not at all to dismiss the reality of antisemitism. But that the antisemitism that does exist today does not generate the same emotional experience that the imaginary form can. Antisemitism today — such as when an arsonist attacks a synagogue or when politicians circulate conspiracy theories accusing Jewish financiers of funding subversive protest moments — often doesn’t have the same straightforward, affective resonance as when someone powerful says there’s a “pogrom” happening in the streets of Amsterdam right now. In Umberto Eco’s Travels in Hyperreality, he wrote about how Disneyland not only produces an illusion of reality but also stimulates desire for this illusion. When you go to a zoo, you can’t find the animals: they’re hiding and it’s boring. But when you go to Disneyland, the animatronic animals are present and exciting. They’re coming out of the water, they’re roaring. The effect actually surpasses the real.

At the Nova Exhibition, there is a particular concern around voyeurism with the way the atrocity footage is arranged into composite scenes of magnified terror with little to no curatorial framing, exposing victims publicly at their moments of extreme vulnerability and humiliation for the consumption of visitors.

You know, there were Jewish college students who toured October 7 atrocity sites in Israel, and then later visited the Nova Exhibition. Some of them said visiting the exhibition was more powerful than visiting the atrocity sites themselves, because at the former you felt you were really there at the festival. The original festival site, in post-atrocity emptiness, cannot facilitate the felt experience that the controlled reproduction can. Similarly, I would say that the real, far more complicated story of what happened in Amsterdam would not have been as stimulating to the public.

The question that we could be asking is how do signs, symbols, and icons of antisemitism (such as the pogrom) deployed in public anti-antisemitic discourse produce a certain thrill? There seems to be an investment in circulating and consuming these narratives of Jewish suffering, a sort of voyeuristic sadomasochism. How is it that fantasies of anti-Jewish violence today are so quickly and compulsively circulated and consumed in public discourse? What is this desire for narratives of Jewish suffering and victimization? At the Nova Exhibition, there is a particular concern around voyeurism with the way the atrocity footage is arranged into composite scenes of magnified terror with little to no curatorial framing, exposing victims publicly at their moments of extreme vulnerability and humiliation for the consumption of visitors.

JB: The room with the shoes, as you describe it, almost quotes the imagery of the Holocaust. I’m curious what it means to think about this within a broader conversation about analogy and relativization. In 2023, famously, Masha Gessen’s Hannah Arendt prize was rescinded when Gessen compared Gaza to a Jewish ghetto. Germany fiercely protects the singularity of the Holocaust, and yet the language of the Holocaust, both literal and visual, has been woven into the discourse around October 7th.

BR: The Nova Exhibition uses specific techniques as emotional shortcuts. The analogy was promoted by the exhibition itself: they shared an Instagram post that literally blends the installation with the pile of shoes at the Auschwitz museum. On the one hand, it draws on the well-known museological icons of Holocaust memory to attract visitors to the memorial, promising a similar sort of dark tourism and emotional catharsis. On the other hand, it reflects the desire to fold the October 7 attacks into a continuous Holocaust narrative, and in doing so create what Ahmed calls a “wound fetish.” The equivalence between the two sets of shoes requires cutting each of them off from the very incommensurable histories of violence and suffering that produced each of them; even on a very basic level, one set of shoes was collected by curators while the other was confiscated from the victims by perpetrators themselves, a difference effaced by the visual analogy.

For me, part of an ethical approach to atrocity memorialization necessarily involves considerable reflection on the perpetrators, the causes and contexts that led to their actions, and the conditions in which we as visitors might be similar to or could become them

In a certain sense, folding the October 7 attacks into a Holocaust narrative seems pretty unsurprising given the role played by Holocaust memory in Israeli national consciousness. But it also appears a little absurd considering precisely what the State of Israel sought to provide Jews in contrast to the helplessness of Jewish victims in Europe. One of the effects of this conflation is to occlude the role and responsibility of the sovereign Israeli state, including the numerous October 7 security, military, and police failures that are well-documented from Israeli sources. By presenting the October 7 victims as helpless Jewish victims of Nazis, the exhibition obscures the actual context quite drastically in order to present a simplistic narrative that ultimately serves the state’s official war propaganda.

For me, part of an ethical approach to atrocity memorialization necessarily involves considerable reflection on the perpetrators, the causes and contexts that led to their actions, and the conditions in which we as visitors might be similar to or could become them. This runs against the common sense of our moment, which is to elevate victim voices and victim narratives, for important historical and political reasons. But if we want to think seriously about prevention, then I think we actually need to reflect deeply about that.

Ben Ratskoff is an assistant professor in the Critical Theory & Social Justice department at Occidental College. He is a member of the advisory board for the Diasporist.