Bait and Switch

Photography: Stefan Korte. Courtesy: The Artist, Arcadia Missa, London and Maxwell Graham, New York.

On a recent winter evening, I stood outside of a Kreuzberg laundromat, at the end of the block where I have lived for nine years. I was washing my new weighted blanket, which I’d bought to combat the anxiety that torments my sleep. As it tumbled, I scrolled through old news.

It’s notoriously hard to discern healthy fear from paranoia. Take the creeping worry that, if push comes to shove, the protections of civil society (free speech, the right to a fair hearing…) won’t hold, and you might find yourself under power’s boot, or just an ambitious politician’s grudge. It’s a worry that has been experienced not infrequently by dissident artists and intellectuals, the players whom society relies upon to maintain a critical vantage on authority. One would like to believe — especially in a country with a past as dark as this one — that such concerns can be filed soundly under paranoia. One would be wrong.

The Wheels of Justice

Last summer, in an investigative report for the German newspaper nd, journalist Pauline Jäckels chronicled the efforts of Joe Chialo, member of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who was at the time Berlin’s senator for culture and social cohesion, to defund a local cultural center called Oyoun. Founded in 2021, Oyoun is, in its own words, dedicated to “artistic-cultural projects through decolonial, queer* feminist, and migrant perspectives.” Chialo’s mission seems to have been triggered by allegations of antisemitism within the organization, particularly surrounding an event held by Jüdische Stimme für gerechten Frieden in Nahost (Jewish Voice for a Fair Peace in the Middle East). These allegations were reported by the Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel, against whom Oyoun has since won two defamation cases. Each attempt to cancel Oyoun’s funding sparked an inquiry. In turn, each inquiry found the allegations insufficient and non-actionable. Not to be deterred, Chialo sent his staff on a legalistic truffle hunt for grounds upon which funding could be cut. In the end, he got his wish.

If and when the history of Berlin culture in the first half of the 2020s is written with integrity, it will largely be a story of right-wing revanchism, through a systematic rollback of the decolonial and pro-diversity advances which shaped the preceding decade.

Chialo, who suddenly vacated his post on May 2, had maintained his course despite warnings issued by his staff. His actions could be interpreted as impinging on free expression, and might pose an existential threat for Oyoun’s 15 employees, some of whose work visas were dependent on those jobs. But the politician’s advisors neglected another danger: By proceeding, a suspicion would be sewn that the accusation of antisemitism was only ever a pretext. In a country where diminishing the Holocaust’s significance is rightfully a grave offense, this alone should make the blood run cold.

In fairness, Chialo was just following unofficial protocol. Legal decisions, we have learned, are to German politicians as don’t-walk signs are to non-German residents of Berlin: suggestions to be considered on a case-by-case basis. A few years ago, the activist group Deutsche Wohnen & Co. Enteignung mounted a successful citizen’s referendum to reappropriate 243,000 corporate-owned Berlin apartments into public ownership. In response, Berlin’s municipal leadership simply delayed the referendum’s implementation until the citizenry got tired and gave up. After the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Benjamin Netanyahu, CDU leader Friedrich Merz —now the chancellor — made clear that the Israeli Prime Minister would still be welcome in his country. Asked in February if he would respect the International Court of Justice’s authority should it find Israel guilty of genocide, the outgoing chancellor Olaf Scholz answered that he would find the decision “absurd.” So much for letting the wheels of justice do their work.

If and when the history of Berlin culture in the first half of the 2020s is written with integrity, it will largely be a story of right-wing revanchism, through a systematic rollback of the decolonial and pro-diversity advances which shaped the preceding decade (that 2010s diversity politics often manifested tokenistically, and that this tokenism functioned to obfuscate unchanging structures of inequality, negates neither their fundamental importance nor the viciousness of the current backlash). It will be a story of one of the world’s most robust urban bulwarks of multiculturalism and non-conformity being sucked into a maw of restricted freedom. This process has had a manifold character. Composed in large part by a local variation of the totalitarianism sweeping the globe, it is also driven by neoliberal policy: a closing of the open city courtesy of a rapacious property-speculation industry that has squeezed out the space upon which free culture — and free thought — depends.

Chialo took office in 2023. During his tenure, this process only accelerated. Now, all cultural organizations need to do to land on the lethal side of political power is shelter global-southern (and especially anticolonial) perspectives. When a brutal program of municipal funding cuts was announced last November, culture was aggressively trimmed, with diversity programs singled out for total gutting. The exhibition “Spectres of Bandung” was set to open in 2023 at Martin Gropius Bau before suffering cancellation by way of terminal postponement. A research-based endeavor, the show was to focus on the 1955 Bandung conference, which congregated formerly colonized nations. For a while, the museum’s website promised new exhibition dates. Then, without a sound, “Spectres of Bandung” itself became a ghost.

The CDU’s defunding of culture is a more politically shrewd variation on the gaudy hatred displayed, in a 2024 Telegram dispatch, from Slovakia’s far-right Minister of Culture Martina Šimkovičová. “LGBTI+ NGOS,” Šimkovičová wrote, “WILL NOT RECEIVE A SINGLE CENT MORE FROM THE MINISTRY OF CULTURE…” It also reflects the Trump administration’s threat to defund public schools which utilize diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in the name of — wait for it — defending civil rights. In the competition for most extravagant derangement of logic, Berlin’s government, which rolls out “anti-discrimination” clauses with the left hand while slashing diversity funding with the right, is putting up a good fight against Trump’s America.

Photography: Guillaume Python. Courtesy of Fri Art Kunsthalle, Fribourg.

The Bait

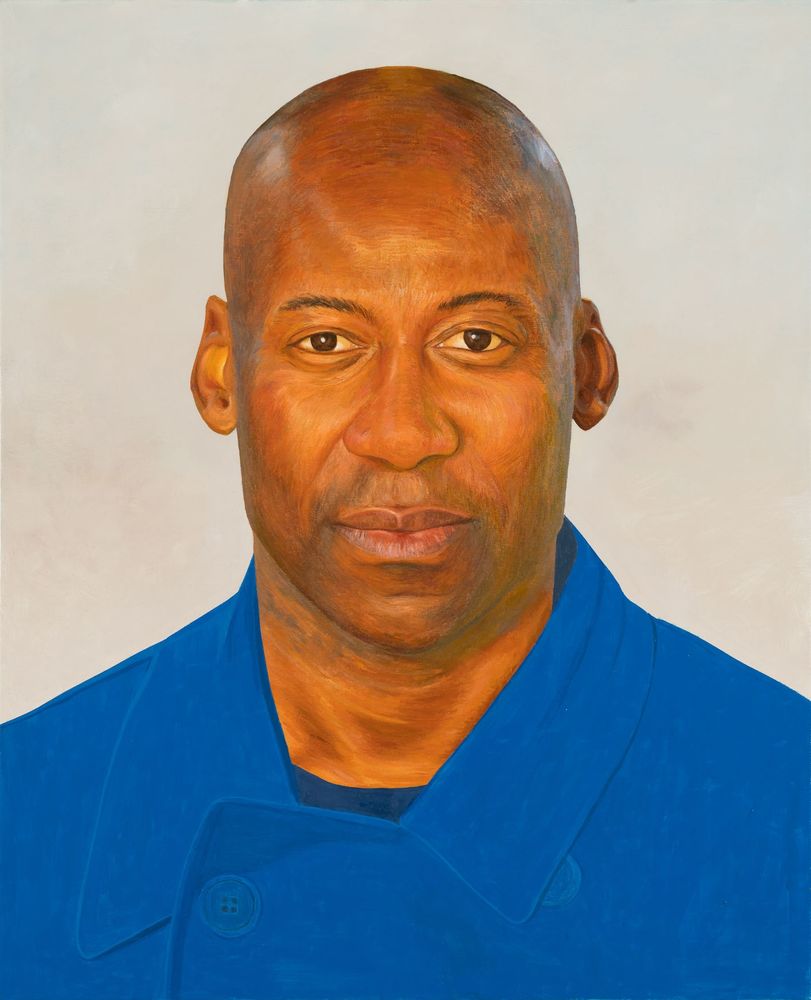

I read Jäckels’ article after attending a talk in early February at Berlin’s House of World Cultures, where author Tobi Haslett spoke about a new oil painting by the Australian artist Hamishi Farah that was meant to have been displayed in this year’s edition of Transmediale, a yearly festival of digital art and culture. Transmediale’s administration had been promised a painting of Michael Jordan, but His Airness never showed up. Instead, Farah submitted a facsimile of the portrait that graces Joe Chialo’s memoir, The Struggle Goes On.

Transmediale found itself having to choose between poisoned baits: reject the painting and brace for cries of censorship, or accept it and risk confirming the suggestion that they were incapable of discerning one Black man from another — while also implicating themselves in a parodic swipe at a politician with a documented taste for punishing disobedient institutions.

If cultural spaces in Berlin would not allow content that engaged with Gaza, they would instead have an image of the man who, in many people’s eyes, holds substantial responsibility for the tactic of prohibiting that content in German institutions.

It is not self-evident why this festival, a hot house of critical media theory, would be a fitting location for this painting in the first place, but Lua Vollaard’s Metropolis M review is instructive: Vollaard speculates that, following 2024’s festival, from which a number of participants withdrew their participation last minute out of protest, this year’s Transmediale was preemptively stripped of content related to the war in Gaza. Vollaard’s claim was seemingly corroborated by conversations with an artist who reported that their scheduled participation in the show had been scrapped, following an admission that their work would engage with Palestine. The festival’s organizers dispute this, citing the inclusion of programming on the topic.

The previous year’s events, and the widespread sensitivity towards this content, can in large part be traced back to Chialo: In December 2023, he had introduced a clause requiring recipients of state cultural support to sign a pledge committing to a “diverse society” and opposing “any form of antisemitism.” But the clause relied on the controversial IHRA definition of antisemitism, which experts had roundly criticized for its lack of clarity. Its tendency to conflate antisemitism with criticism of Israel, they warned, weakened the fight against antisemitism. In ensuring that all criticisms of Israel could be considered antisemitic, without qualification, the clause seemed designed to exacerbate an already disastrous chilling effect on free political speech. Following an open letter of protest, signed by over 4,000 cultural workers, it was binned.

All of this has unfolded in the tailwind of the 2019 Bundestag resolution “Resisting the BDS Movement with Determination,” which precedes Chialo’s tenure. Introduced by a coalition of centrist parties (directly in the wake, it should be remembered, of a similar, failed proposal from the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD)), the resolution forwarded a prohibition on supporting groups aligned with the BDS movement. Though legally non-binding, the resolution triggered institutions to terminate their associations with artists suspected of supporting the boycott. It is in this context of soft back-room censorship that both artists and journalists feel justified in maintaining skepticism about institutional responses to certain topics in their work.

The attempted display of Farah’s painting, therefore, followed a Trojan horse logic. If cultural spaces in Berlin would not allow content that engaged with Gaza, they would instead have an image of the man who, in many people’s eyes, holds substantial responsibility for the tactic of prohibiting that content in German institutions. Eventually, the horse made it halfway in: Transmediale’s organizers agreed that Farah’s painting could be present during Haslett’s talk, but only then.

Photography: Tom Bowditch. Courtesy of the artist, Arcadia Missa, London and Maxwell Graham, New York.

The Switch

“Hey Joe,” I thought, when I came face to face with Farah’s painting: “What are you doing with that look in your eyes, staring into the middle distance?” The image finds Chialo’s shoulders and chest draped in a heavy, collared coat, somewhere between cerulean and cobalt blue. Chialo’s head drifts in a background of sallow white.

Farah’s painting is a mocking iteration of court portraiture. This is implied largely by the manner of its appearance at Transmediale. To put it mildly, Haslett’s talk took a skeptical position on Chialo’s contribution to the defense of human rights and free speech. Given that the talk was organized in collaboration with the painting’s curator Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung, the bait and switch seemed to be a collaborative provocation. But in its dumbstruck plainness, and its absurd recitation of a politician’s PR photo, the work is more subtly barbed.

In 1996, South African author J.M. Coetzee released his book Giving Offense, a collection of essays on censorship. A passage from its lead text could have been written to accompany Farah’s canvas. “The more closer the imitation,” Coetzee writes,

the more immediately and irresistibly it evokes laughter in the onlooker. Simply by virtue of their prominence, the powerful become objects of imitations which mock or seem to mock them, and which nothing but force can suppress. Yet the moment they act against these representations as the misrepresentations they intrinsically are, they betray (or seem to betray) a vulnerability to mockery.

This is the double bind presented to Chialo: the poisoned bait, if he takes it, shows he’s squarely outside of the joke.

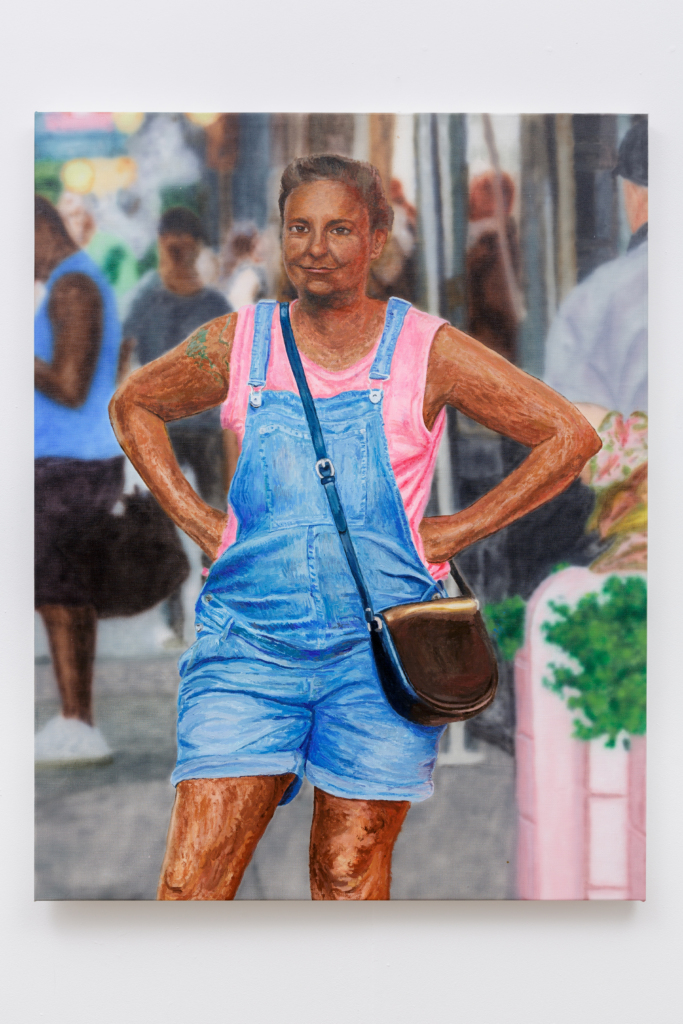

The Chialo painting was not Farah’s first outing as painter-troll. His most well-known canvas, “Representation of Arlo” (2018), portrays the son of American painter Dana Schutz. That piece was a reaction to Schutz’s most infamous work, which adapted a sacred piece of evidence from the American civil rights struggle: the open-casket photo taken of Emmett Till, the Black teenager lynched for allegedly flirting with a white woman. That gaffe got Schutz, who is white, raked over the hottest coals of late 2010s call-out culture. Her worst mistake was a blinding misapprehension of the meaning inherent in her cartoon expressionist way of painting and its ill-fittedness to her subject. She must have believed that her sculpted strokes of thick paint would movingly resonate with Till’s decimated face. Instead, they made racist murder into painterly fetish.

If the potential for misapprehension is a scary reality of being human, it is a necessary condition of art. Farah’s response to Schutz’s painting shows her child sitting up, facing the camera head-on. Although the child’s downcast eyes might seem to protect his soul, the position also underlines his lack of agency, both vis-à-vis Farah and also the apparatus of contemporary image harvesting. In this way, “Representation of Arlo” brings the mind to many unexpected places.

Farrah’s Chialo painting did the same. As Haslett’s talk receded into the memory of winter, I became less sure if the senator’s dull gaze suggested power as such, or something deeper and darker. A sad relishing in power, maybe — but also a corresponding blindness to the awful consequences of that compulsion; consequences that first afflict the powerless, but that also, inevitably, meet the powerful themselves, mangling their psyches, deforming their perception of justice, and the preciousness of life.

On the morning of May 2, a strange thing happened to Farrah’s painting. It suddenly became a portrait of reckless authority, as seen in a rear-view mirror: lost, vacated, deposed, or used up.

“I have asked Berlin’s ruling mayor,” Chialo wrote in a dispatch released that morning, “to dismiss me from my position as Berlin’s Senator for Culture and Social Cohesion.” Taken at face value, this was a decision made of conscience. The further cuts planned by his party, Chialo explained, would be too deep, presenting a dire threat to Berlin culture. Furthermore, tensions between him and his constituents had made productive conversations untenable. These were unexpected words from the mouth of a man who had repeatedly cold-shouldered overtures to dialogue. As Jäckels reported, Oyoun had on several occasions reached out to Chialo’s office, asking for a discussion.

So what about Chialo’s legacy? No reasonable person could say that his work has consolidated the strength of culture or fostered “social cohesion.”

Given these inconsistencies, a speculative observer might ask if this was a resignation, or a “resignation.” Following the CDU’s national election victory, Chialo had been the presumed successor to Claudia Roth as Germany’s minister of culture, but on April 28, Chialo’s party announced that this position will instead be filled by Wolfram Weimer, a conservative editor and publisher with exactly zero experience in either politics or culture. That same speculative observer might also wonder if Chialo’s own political career has just fallen victim to the political ruthlessness whose agent he had willingly become.

Photography: Tom Bowditch. Courtesy of the artist, Arcadia Missa, London and Maxwell Graham, New York.

Art and Power

All of which brings back an uneasiness that I remember feeling during Haslett’s talk. Although I agreed with most of what he said, and laughed out loud at the Michael Jordan bit, I also realized I was in a real-life version of the online echo chambers that have disastrously reduced debate into streams of self-assured opinion. Sitting on stage, glaring slightly under overhead lights, Chialo’s head became a meme — easy fodder for an audience hungry for the cathartic naming of a common enemy. It would be too generous to call Chialo a scapegoat. But the individualized logic of critique embodied by Farah’s painting serves much the same purpose: reprieve from the formidable challenge of engaging power as it is actually articulated — which is to say systemically and across the neoliberal-conservative-right-wing spectrum.

Given how formidable that project is, Farah’s painting also communicates desperation, of the sort that tends to drive indignant hectoring. Yes, the work is a portrait. But it’s also, in a strangely generative sense, a symptom of the seemingly impossible situation we are in: namely, the challenge of supporting the unquestionable German (or just human) responsibility to guard against antisemitism, while also having to fight off the dismantling of constitutional rights via the censoring of protest against Israel’s decades-long illegal occupation of the West Bank; its violent immiseration of life in the Gaza strip; and now, following Hamas’ hideous crimes on October 7, 2023, the Israeli military’s unremitting slaughter of innocent Palestinians, as well as its scorched-earth obliteration of Palestinian culture and infrastructure, including schools and hospitals.

So what about Chialo’s legacy? No reasonable person could say that his work has consolidated the strength of culture or fostered “social cohesion.” To the contrary, animosity and mistrust now reign between the significant, politically committed portion of Berlin’s cultural scene and German institutions. For the former group, Chialo will always be the man who attempted to do the right wing’s dirty work through a structural prohibition on legitimate political protest in culture. The face in Farah’s painting will be recalled as the cultural agent in an apparatus of state repression.

At the moment, deportation proceedings are ongoing against four activists ordered by the government to leave Germany or be forcibly removed. None are accused of a crime, much less convicted, and there is little doubt that the deportations are extrajudicial punishment for standing with Palestinians; the list of artists, writers, and activists who have been censored in Germany has grown so long as to scramble the average person’s capacity for engagement. Police brutality against activists has been frequent and well documented. While polls repeatedly find that a majority of Germans oppose Israel’s actions in Gaza and the West Bank, demonstrations to this effect are conspicuously thin on white Liberal German participation.

It follows that if artists and art institutions want to keep existing, and especially if they want to keep existing as agents of progressivism, their politics of diversity will need to take the only form a true politics of diversity can, by becoming rigorously braided with a politics of class.

Among the conclusions that can be drawn from recent attacks on arts funding is that the adage that “all art is political,” despite being a cliche, is unshakably true. As Sarah Schulman pointed out during a talk at Oyoun last year with the journalist Ben Mauk, it is precisely the arts that have become a battleground for free expression. The right wing has confirmed this political meaning of art. It has done so by making a public sacrifice of two groups easily cast, amid gaping inequality and disastrous inflation, as enemies of the impoverished and overworked local people: publicly funded artists and art institutions, implicitly understood as a decadent and spoiled elite, and foreigners, perennially understood to be thieves of work and destroyers of local (read: white, German) culture.

It follows that if artists and art institutions want to keep existing, and especially if they want to keep existing as agents of progressivism, their politics of diversity will need to take the only form a true politics of diversity can, by becoming rigorously braided with a politics of class. That will, in turn, also require art’s subtle, comedic, morally complex behaviors.

Crying and Laughing

In his 1991 essay “Tart Wit, Wise Humor,” the American art critic Donald Kuspit argued formidably that the historical avant-garde has been, at its core, “an eloquent rearticulation of the comic spirit.” “To be avant-garde,” he wrote, “is to pursue, through the deliberate development of a comic sensibility, psychic rebirth—optimism rather than pessimism, despite recognition of the world’s unpleasant reality.” Then as now, “unpleasant” would be putting a genteel spin on things.

A weighted anxiety blanket can’t do much against the fear inspired by the trial-run despotism, which Germany has experienced lately. In a recent nightmare, I found myself hunted by a ruthless apparatchik. This, of course, is how censorship does its craven work, haunting dreams and crippling moral thought. Over every hand raised in protest, threats loom. Think of your career. Think of your German residence permit. Think of the life you’ve built here. Meanwhile, anxiety creeps, vocal cords stiffen, and democratic norms atrophy.

Somewhere in all of this, maybe, there is a place for artistic gags and laughter — if only in response to power’s insanity, and as long as it’s the kind of laughter which staves off callousness and disturbs silence. As someone once said, the struggle goes on.

May 20, 2025: This piece has been updated to reflect conversations with Transmediale’s organizers and participants around the content of this year’s festival. Additionally, an earlier version of this text incorrectly stated that SAVVY Contemporary had lost 50% of its funding. After a threat of 50% to 100% in reduction of funding, SAVVY Contemporary did not lose their funding for this year.

Following the publication of this article, Transmediale reached out to the Diasporist with the following note: transmediale is pleased to have commissioned the project ‘On a Painting’. We recognise the presentation was subject to last minute changes led by the project’s curator Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung, and applaud how this change in content and form allowed the project to powerfully highlight the absurdity of the German context. This position was further amplified across the 2025 festival edition through diverse programming that directly engaged with political positions currently under threat in Germany and elsewhere.