When the Lights Go Out in a West German Talk Show. Ask Max

Translated from German by Michael Saman

Editor’s note: The following text is from a lecture-performance that was originally presented at “Der grosse Kanton: Rise & Fall of the BRD,” which was held in Zurich on 5-6 December.

ONCE AGAIN YOU STAND at the beginning. At the beginning of a day, of a conversation, of a story; a beginning in which, as always, multiple beginnings intermix despite being in the singular. Only this time you no longer have the confidence that Foucault did at the beginning of The Order of Discourse that you must go on speaking — that you must say words until they find you. This time, what finds you are not words, but a mourning that has not yet found its equivalent in words. You seek refuge in sleep and turn to The Book of Sleep by Haytham el-Wardany. You read that in the darkness one world departs and another takes its place. This does not keep you awake, but you do not fall asleep either. “Things knit into their surrounds” and you begin to be open to intermixing and contradiction.

What begins more than once promises a loss of clarity. That’s good. You do not wish to conjure a now that sets itself sharply apart from before and after, and claims to be current. You want to look into the face of a world that takes the place of another and veils clarity, even if it has no face, or multiple faces. Neither awake nor asleep, you cannot see whether it is a darkness that recurs thanks to the earth’s rhythms, or a solar eclipse that only temporarily covers the sun’s light. The loss sets you into a recurring motion similar to the little experiment that Max Horkheimer once proposed on a West German talk show. He went onstage with a stack of old newspapers, laid them down next to his chair, and announced that he would answer the moderator’s questions by reading aloud from the newspapers. You don’t know if this story is true or whether it only becomes true upon being told. Open to the interference of the past in the present, you embark on the experiment.

Herr Horkheimer, the Viennese author and founder of political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, made a promise in his 1896 book The Jewish State: “We [Jews] should there [in Palestine] form a portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.” From his conversation with Friedrich I., Grand Duke of Baden, Herzl concluded that this intention is harmonious with German political interests, and noted in his diary: “With the Jews, what would come to the Eastern coast of the Mediterranean is in fact an element of German culture.” You, Herr Horkheimer, belong to what Zionism regards as the frail diaspora Jews who could only attain sovereignty in the Jewish nation-state. Yet fifteen years after you fled from Nazi Germany you remigrated to the Federal Republic. What brought you to choose the diaspora over the Jewish state?

The talk show guest slowly turns in his chair and pulls a copy of Der Spiegel from the year 1965 from his stack of newspapers. He opens the magazine to an article titled “Mother’s Milk” — which deals with the state of Israel — and reads:

“The population of Israel is divided into a lighter-skinned European minority of 40% and a darker Oriental majority of 60%. The two groups are not connected by much more than religion and their common Biblical history prior to the Diaspora. The white Israelis have proper schooling; the dark Israelis often cannot even read and write well. The whites are prosperous; the dark ones are poor. The whites live in big cities and on cultivated land; the dark ones in the new towns of the province and on underdeveloped land. The whites practice the leading professions; the dark ones the subordinate [professions]. The whites are self-confident; the darker ones suffer from a deep inferiority complex. [White Israelis see themselves] in the Jewish colony of Palestine […] as threatened by the ‘danger of Levantinism’ and wish for a fast-track assimilation of their backward religious brethren.”

Herr Horkheimer, the assimilation of the German Jews before 1933 is considered to have failed. If I understand you correctly, white Israelis, who tried unsuccessfully to assimilate themselves into Western Europe, now want to assimilate their “backward religious brethren” from the Arab diaspora. Israel’s Prime Minister was recently quoted as saying that he intends under any circumstances to “prevent Levantinism from creeping into [Israel’s] national life!” For our viewers, let us add that the term ‘Levantinism’ was first used after the founding of the state as a synonym for the backwardness of Arab Jews and as a threat to national life. In the prewar era, French and British colonial masters used the term disparagingly to designate the multiethnic minority culture they encountered in the Near East and North Africa. They were unable to identify this as either the Oriental culture of their imaginations or their own Western culture. It seemed to them to be a mixed, impure culture that imitates the West in order to feign a false belonging. Herr Horkheimer, why does a mixed culture such as the Levantine one represent danger to the formation of a nation? And can a one-sided assimilation such as France’s civilizing mission in Africa or the one that Israel is striving for put a stop to this danger?

Without remarking that he is about to break with his rules, the guest begins to read from a newspaper dated from the future:

“Germany’s ambassador in Tel Aviv spoke with Haaretz about German responsibility, especially post-October 7, 2023, as opposed to German guilt.”

The camera pans abruptly to the audience, where a young woman, who presents herself as a history student, interrupts the guest:

In your book Critique of Instrumental Reason, you describe “the growing apparatus of mass manipulation” that is reminiscent of social engineering projects, not least Israel’s demographic policies. When, following the Holocaust, it became clear that no mass migration of European Jews into the country could be expected, Zionism began to take an interest in the Arab Jews. Israel’s reconceptualization of Jewishness as a national identity had profound implications for Arab Jewish immigrants. In the name of a melting-pot policy, they are expected to leave their Arab history behind them. Their knowledge of the Arabic language is employed for Israeli intelligence rather than for dialogue with their countries of origin. With the founding of the state, the possibility of being both Jewish and Arab was “relegated to the past.” They must assimilate themselves to a present in which Arab culture is reserved for portraying the non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine as an enemy stereotype. “The Orientalist splitting of the Semite [is] now compounded by a nationalist splitting.” Scholars are researching the question of how the Zionist conception of Jews and Arabs as exclusive and antagonistic ethnic categories differs from the Nazi German notion of mixed marriages as a threat to the German nation.

The student’s comment seems increasingly to resemble the kind of comment where, under the guise of asking a question, someone is actually thinking aloud. But then there does follow a question:

Would it not be more urgent to call into question the way Western scholarly culture makes partitions in the name of clarity, which allows it to define the areas of research from which disciplines, professionalism, and specializations emerge?

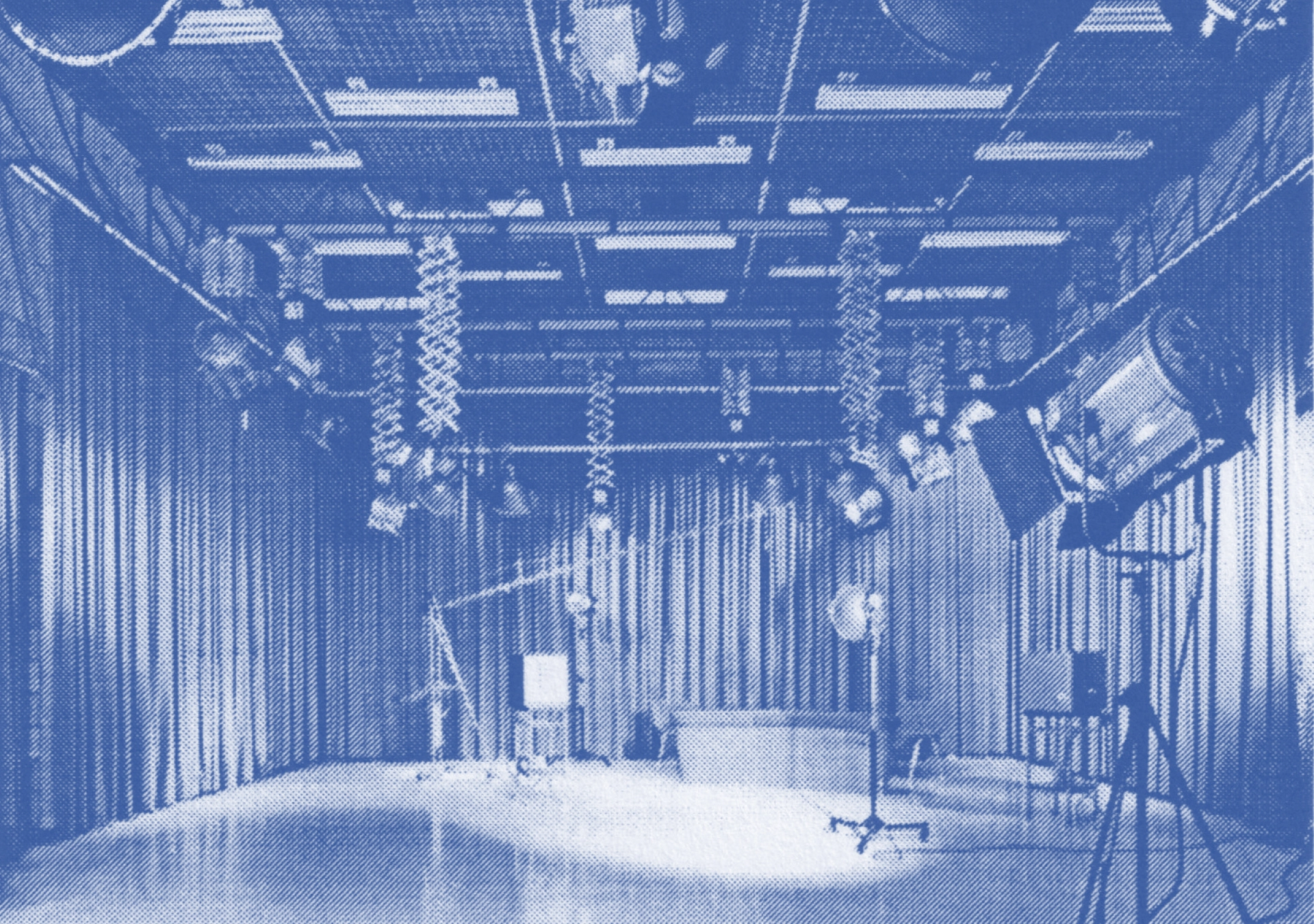

The television studio goes dark. The following day, the press will speculate as to whether the studio technicians shut off the power as an act of sabotage. Max Horkheimer himself is alleged to have discussed the move with the technicians. As soon as the German title of his book Eclipse of Reason was mentioned in the discussion, the experiment was to be interrupted. Eclipse of Reason had recently been translated into German as Critique of Instrumental Reason. The eclipse in the book’s English title was thereby taken out of the picture; this is regarded as the German Federal Republic’s departure from cosmic orbit.

Does the darkness signal the end of the talk show or will it compel the guest to speak freely? The beam of a flashlight appears on the stage and jolts you out of your thoughts. Horkheimer appears to be well prepared for the occasion of a power outage. He reads further from the interview with the ambassador.

“Haaretz: [We would like to conduct] a short interview … about … Holocaust [Memorial] Day for the weekend magazine […], if it’s okay with you.

Ambassador: It’s okay with me. Okay, so about [Holocaust Memorial Day]?

…

Haaretz: I wanted to ask if you, Germans, feel that Israel is … [t]aking advantage of your feelings of guilt about the Holocaust?

Ambassador: First and foremost, it is not about feelings of guilt, because nobody in my generation or younger has any personal guilt in this. When we remember the Holocaust […] [w]e do it because we feel responsibility and we feel our country has drawn lessons from it, and must continue to draw lessons from it.

…

Haaretz: […] Is it possible for Netanyahu to land in Germany without being arrested?

Ambassador: First you ask me about an interview about [Holocaust Memorial Day], and now we are at that question. This is, I would say, disingenuous, to put it mildly. […] This is not a question in any way related to [Holocaust Memorial Day].”

Herr Horkheimer, following the ambassador’s order of discourse, the mixing of these questions is disingenuous, and the separation of guilt from responsibility has been unambiguously established. If I think of the conversation between Margaret Mead and James Baldwin that recently appeared under the title A Rap on Race, then mixing and separation are also culturally conditioned. “There are different ways of looking at guilt. In the Eastern Orthodox faith, everybody shares […] the guilt for anything anyone ever thought. Now, the Western […] position on the whole is that you’re guilty for things that you did yourself and not for things that other people did.” A division between acts of one’s own and those of others is necessary for jurisprudence, but what ethical role does this division ascribe to people who are neither the direct perpetrators nor the direct victims of an act, but rather onlookers or accessories who must live on with the norms set by this action?

“Tel Aviv, August 3, 1963.

Having followed with great interest the controversy between representatives of Israel’s Oriental and Ashkenazi intelligentsia in [your journal], I would like to add [a comment], particularly in reference to the article […] about ‘Black Zionism and the Fear of Assimilation.’ I was startled by the parallel between African Americans, with all due respect for their just struggle, and the situation of Oriental Jews in Israel. The last thing that should have happened to the Jewish people in Israel is to split along a color line, even if this is, somewhat prudishly, labeled “cultural” rather than ethnic. […] James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time, refers to the God revealed to a Semite desert people “before color was invented,” and this apt phrase is something we might ponder. […] Perhaps some European Christians imagine that God, incarnate in Christ, is white, so that Africans, liberating themselves of the white Man’s yoke see Him as black. But to Jews, the idea of God never found incarnation in a body. From the outset, God was represented as a voice humans may hear. […]”

— Jacqueline Kahanoff, letter to the Jewish Observer and Middle Eastern Review.

In your thoughts, the darkness in the television studio overlaps with the black screen of a television. For the viewers at home, the black screen is illuminated by a block of commercials — Persil, Boss, Nivea, Dual, Mercedes, Adidas. The moderator doesn’t want to acknowledge the darkness and drums on the microphone with her fingernails. The taps remain inaudible, yet seem to conjure Horkheimer’s next answer. The rhythm of his speech suggests that he is translating extemporaneously into German.

“It was an advertisement in a Stockholm paper. ‘English-speaking young man,’ it read, ‘wanted as private chauffeur. Must be cultured,’ it said. I went to the Grand Hotel, all my culture in the tip of my tongue and all my English waiting to be spoken. Hungry? No, but insecure and frustrated in my attempts to be given a job; and terribly in love.

I asked for Mr. Jones at the desk. He was just coming out of the lift: a bald-headed man, pleased with himself and comfortable looking.

‘‘Allo, son,’ he said, ‘come and ‘ave somethin’.’ I followed him to the bar, optimistic and pleased with the ‘allo, son.’ […]

‘Ever drive a Daimler?’ he asked, [nodding towards the Mercedes parked in front of the entrance].

‘No, sir,’ I said truthfully.

‘Wanna get on in life, […] say yes. Daimler same as any other bloomin’ car.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Don’t let nothin’ scare you.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Need someone for the Daimler. Drive the wife about town. Some Swedish for doin’ the shops.’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

‘Fifteen quid a week,’ he said, and winked at me.

I took a glass of champagne. It swelled in me and soared high up, up above the Grand and over the port; high enough to see Helsinki at a distance. He told me he was a self-made man. Started with peanuts and worked his way up to all this. He waved his hand at all this and I looked and thought of the [Mercedes] and the champagne, and wondered if perhaps … but I remembered a peanut vendor I know who is going to be a peanut vendor all his life.”

Horkheimer pauses a moment. The moderator jumps in and asks, in an empathetic voice, how the job interview ended. The audience can read the full account in the Guardian from November 24, 1958, says the guest. The headline is “Culture for the Daimler.” I would be inclined to add a note about the author from The Times.

“Waguih Ghali, the Egyptian whose report […] we print on this page, is a bearded Copt…”

What does the beard have to do with it?, wonders the guest aloud before continuing, interrupting himself repeatedly when a detail doesn’t seem right to him.

Waguih Ghali… left Egypt in 1958. He stood far to the left of Nasser, was targeted by the authorities, and his arrest seemed to be only a matter of time. After spending time in Paris, London, Stockholm, and Hamburg, he settled in Germany… in West Germany, “which is much less demanding than [Britain] when it comes to work permits.” He lived in Rheydt, near Düsseldorf, and worked in the office of the British Army of the Rhine… and in a factory. Together with other leftists there, he exposed the Nazi affiliations of the mayor, and he wrote his novel Beer in the Snooker Club. “He is multilingual and moves easily from Arabic to French or English.” He is currently working on a novel that takes place in 1965 in an unspecified city in “the greatest postwar ‘miracle’ economy.” The protagonist Ashl is a guest worker… an intellectual of unknown national origin who works as a translator for a publishing house. It remains to be seen whether Ashl will have similar experiences to those of his author, who plays tennis with friends, goes to bars, and is confronted with attitudes such as that of his friend Kurt, who is now together with his ex-girlfriend Liselotte but will never marry her because she was previously together with “AN EGYPTIAN.”

In 1967, after Israel’s war of occupation, Ghali went to Israel on a journalist’s visa. “The Israelis seem to remember the past only when it is to their advantage,” he stated to the BBC. They would often quote the anti-Israel speeches of the Algerian president while forgetting “that Israel supported France during the Algerian War” with intelligence about the FLN.

A year later, at a conference in London where Ghali speaks about Israel and Palestine with a member of the Israeli anti-Zionist organization Matzpen, he becomes stateless. A representative of the Egyptian government rises from the audience and declares that, contrary to what is indicated on the conference poster, Mr. Ghali is no longer an Egyptian but has defected to Israel. In the postcolonial order of nation states, his temporary West German residency permit is all he has for the moment.

Herr Horkheimer, a member of the Coptic minority in Egypt, who shares a podium with the Israeli anti-Zionist diaspora in London; who earns his living in a factory in West Germany; who publishes a novel in English, the protagonists of which flee Egyptian nationalism to an idealized Europe that bitterly disappoints them — is this the Levantine who endangers our nation’s democracy? Or can our Daimler culture assimilate itself to such a heterogeneous and diffuse mixture of loyalties?

This is against the backdrop of Germany having converted its historical guilt into monetary language and amortized it, and having so masterfully simulated its renunciation of Nazi theories about mixed races that it once again appears attractive to people from other countries. With our labor recruitment agreements, we invite foreign workers to attempt their socioeconomic climb in the Mercedes assembly shops. In this way, we quite closely follow the example of France, England, or the Netherlands, who grant rights of citizenship to the immigrants from former colonies who today shape the minorities in Western Europe. The Jewish-Arab author Jacqueline Kahanoff goes so far as to suggest that the concept of the nation-state, however modern and progressive it may appear, might already be obsolete if viewed in global terms. After all, in the 1920s the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld viewed what we regard as national culture as being the result of processes of mimicry. Seen in this way, Levantine culture would continue a process of mutual assimilation that has always been ongoing. It is sand — not oil — in the gears of global national culture, is it not?

It must already be daylight outside. The moment that you say this, it occurs to you that you can scarcely distinguish any longer between inside and outside. No, this binary no longer offers you a way out. Seeking refuge in sleep, you have erred into temporal spaces beyond the present moment, where you end up every time you abide by rules that were made up at some point in time, and not for you personally. In this mixing of space and time, your sense of time gets lost and you encounter yourself anew, as a different person. Whether the talk show guest answers his interviewer’s questions with reports out of newspapers from the past or from the future is no longer of importance to you. You have come under the spell of his recurring movement, in which narratives weave themselves into the present in such a way that you can no longer make sense of presence in the singular.

Onstage, the beam of the flashlight moves aimlessly through the air while the guest rummages with one hand through his stack of newspapers. He seems to recall a particular article that he thought at some point would be valuable to read again in the future —which could be now. A memory that stores things away without specific intent appears to be part of this experiment. Perhaps this experiment has to do with a way of thinking that does not identify its intentions in advance. A sort of disrupted universalism that Kahanoff ascribes to a Levantine way of knowing, for which “a person, however worthless, counts more than principles, however sacred.” A way of thinking that is subject neither to chance nor to intention, and that, in accordance with the situation it finds itself in, reaches back to voices that are reenacted and that let the guest appear as someone else with each answer. In any case, this is how it appears to you when Max — or Horkheimer — gives up rummaging through his newspaper pile, turns his flashlight off, and begins speaking as if again he were translating on the spot; this time from memory, which could be from Leonore Sterling’s 1965 article in Die Zeit, or from the future:

What is new in the ‘new Germany’ is “the antisemitism of philosemites.” “One distances oneself emphatically from the more or less open antisemitism of far-right circles,” and feels oneself thereby to be “self-righteously pure and pro-Jewish, [albeit] without having made the effort to examine oneself internally.” The repressed contradictions are then overlaid with “philosemitic” idols that associate Jews with “intellect,” “culture,” “suffering,“ or “victimhood” — and right away one feels legitimated in transferring the suppressed anti-Jewish prejudices “at least partly onto other objects of hate.” “Through this transference,” the contradiction finds “a way out. Those affected in the Federal Republic are always minorities whose disparagement and open persecution do not, in the eyes of ally nations, imperil the erected symbols of German democracy, either because there they are likewise objects of hate or because they are not considered significant enough to stand as litmus tests for democracy in Germany — Eastern Europeans, so-called leftist intellectuals, and guest workers. When, for example, leading politicians speak of ‘rootless leftists,’ of ‘corrosive and unprincipled literati’ who ‘soil their own nest,‘ or even of ‘leftist Protestants‘ who stand in conspiratorial union with the ‘Antichrist,‘ then indeed all that is missing [is a designation like] ‘Jewified‘ — and we would once again have a solid and official antisemitism. The notions […] of Italian ‘skirt chasers’ and Turkish knife-wielding thugs evoke memories.”

“The philosemitism that is so diligently propagated in the Federal Republic […] actually has less to do with Jews and more to do with Staatsräson and foreign policy.” In order for philosemitism to become an instrument of foreign policy, the Biblical status of the Jews as the chosen people had to be carried over to the state of Israel. God, who only had seven days to create the world, was not able to bring about this transference, but the ‘new Germany’ can. The obligations that the people of Israel took upon themselves with their Biblical chosenness are thereby accredited to the state of Israel as “special rights.” Whatever the cost. With the reparation payments, money was cultivated as a remedy that not only helps the victims, but also abstracts the guilt that preceded the payments into exchange value so that for the perpetrators as well as for the victims and accessories, the cause of the guilt, were it to recur in other connections, would merely appear as a further loan being taken on.

The new German philosemitism has more to do with purchased approval than with atonement for something that cannot be set right with money. Philosemitism buys the subjects of its desire, and if these do not correspond to its means or ends, they will simply be adapted, assimilated — whether alive or posthumously. Just think of Gabriele Tergit. Every few years, this one-time Berlin author is rediscovered in Germany — but not her political essays on Palestine, the country that she left in 1938 after five years because she could not countenance “nationalism in any guise.” “You see,” she wrote to her colleague Hans Jaeger in 1974, “my anti-Zionism has cast more of a shadow over my life than racism from Germany has.”

But in this darkness, how would one be able to see shadows?

⎯ Michel Foucault, “The Order of Discourse,” Inaugural Lecture at the Collège de France, given December 2, 1970. In: Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader, Robert Young, ed., Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981. ⎯ Haytham el-Wardany, The Book of Sleep, London: Seagull Books, 2021. ⎯ Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State, New York: Dover Publications, 1988; Theodor Herzls Tagebücher, vol. II, Berlin: Jüdischer Verlag, 1923. ⎯ “Milch der Mutter,“ Der Spiegel, 31/1965. ⎯ Manchester Guardian, February 6, 1961, sec. 8/2. Quoted after Gil Z. Hochberg, “‘Permanent Immigration‘: Jacqueline Kahanoff, Ronit Matalon, and the Impetus of Levantinism,“ boundary 2 31:2, 2004. ⎯ “German Ambassador to Israel Steffen Seibert: ‘We Have Doubts About the Resumption of the War,‘“ Interview by Nir Gontarz, Haaretz Online, April 24, 2025. ⎯ Margaret Mead and James Baldwin, A Rap on Race, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1971. ⎯ Max Horkheimer, Eclipse of Reason, New York: Oxford University Press, 1947. ⎯ Jacqueline Kahanoff, Letter to the Jewish Observer and Middle Eastern Review, August 3, 1963, Jacqueline Kahanoff Archive, Heksherim Institute and the Literary Archives at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er Sheva. ⎯ Avi Shlaim, Memoirs of an Arab-Jew, London: Oneworld Publications, 2023. ⎯ Ella Shohat, On the Arab-Jew, Palestine, and Other Displacements: Selected Writings, London: Pluto Press, 2017. ⎯ Waguih Ghali, “Culture for the Daimler,“ Manchester Guardian, November 24, 1958; The Diaries of Waguih Ghali: An Egyptian Writer in the Swinging Sixties, May Hawas, ed., vols. I and II, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2016/2017; unfinished manuscript, 1969, ecommons.cornell.edu; “An Egyptian in Israel,“ in: Good Talk: An Anthology from BBC Radio, Derwent May, ed., New York: Taplinger Publishing Company, 1969. ⎯ “The Times Diary”, The Times, August 10, 1967. ⎯ Pankaj Mishra, “Beer in the Snooker Club: Introduction,“ LA Review of Books, June 8, 2014. ⎯ Jacqueline Kahanoff, “Europe from Afar“ and “Afterword: From East the Sun,“ in: Deborah A. Starr and Sasson Somekh, eds., Mongrels or Marvels: The Levantine Writings of Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff, California: Stanford University Press, 2011. ⎯ Günther Eich, Träume, Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk, 1951. ⎯ Karsten Witte, “Straubs Publikum,“ Kirche und Film 19, Nr. 3, 1976. ⎯ Leonore Sterling, “Judenfreunde–Judenfeinde: Fragwürdiger Philosemitismus in der Bundesrepublik,“ Die Zeit 50, December 10, 1965. ⎯ Gabriele Tergit, Letter to Hans Jaeger, December 3, 1974, Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach. Quoted after Elke-Vera Kotowski, “Im Schnellzug nach Haifa und Der erste Zug nach Berlin. Gabriele Tergits Reisepässe als Dokumente ihrer Exilerfahrung,” Text + Kritik, Heft 228, 2020.