Reconsidering the Oyster

Translated by Martha Turewicz

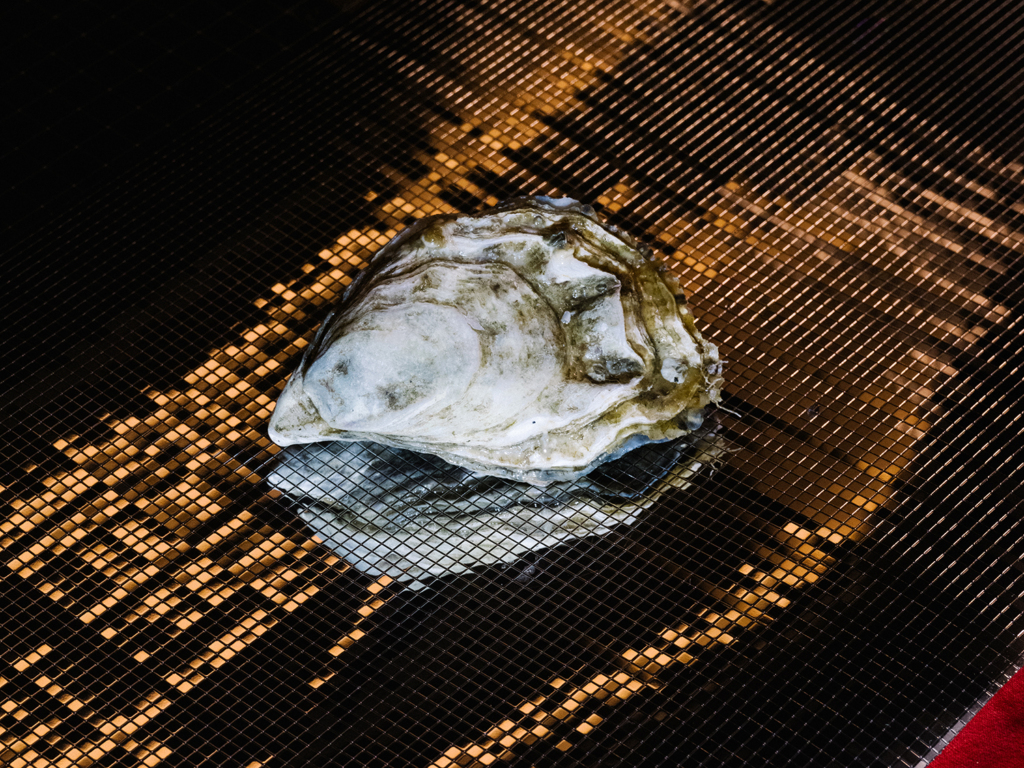

The five of us are seated at the bar for diners in FrischeParadies, a gourmet grocery store in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district. Each of us faces a plate of six oysters on a bed of crushed ice. Their gnarled tops have been removed, and the gray-brown flesh those shells concealed gleams beneath cool fluorescent lights. The oysters are laid out like the numerals on a clock; the twelve o’clocks are garnished with thin lemon slices. We chase each oyster with a sip of champagne, then proceed to the next oyster-numeral along our dials. As we eat, we listen to the friendly fish counter expert describe our meal. We could certainly get used to this: oyster, Champagne, oyster, Champagne. We feel a joyful rush.

“An oyster,” wrote M.F.K. Fisher in Consider the Oyster, “leads a dreadful but exciting life.” For two weeks, the small oyster larva lives out on the open sea, until it adheres to a solid surface and undergoes a metamorphosis of sorts. Incidentally, the oyster is a hermaphrodite—Pacific oysters typically change sex once in a lifetime, whereas European oysters do so continuously throughout their lives, which can span up to 30 years.

Not all young oysters survive. A great deal of energy is required to form the calcified shell that later provides cover from predators. The more an oyster is forced to fend off intruders, the stronger its muscle grows—which makes said oyster more difficult to ultimately pry open. This development also yields more full-bodied flavor.

The end of an oyster’s life is determined by where it is eaten. In China, where the most oysters worldwide are farmed, they are almost always cooked, for dishes such as the oyster omelette known as dan jian sheng hao. As such, they die in the pan. Meanwhile, in the U.S., they’re topped with melted butter and herbs, then baked to prepare Oysters Rockefeller. In Europe, they’re usually eaten raw, which means they meet their ends somewhere between the eater’s mouth and throat. “[Their] life,” Fisher summarized, “has been thoughtless but no less full of danger, and now that it is over we are perhaps the better for it.”

In 2003, Gourmet magazine sent David Foster Wallace to the Maine Lobster Festival; the resulting piece is titled Consider the Lobster, in homage to Fisher’s book. Wallace had an entirely different agenda, however: instead of delighting in consumption, he wished to encourage readers to recognize the lobster as a living being capable of feeling pain. Wallace never stooped to eating lobster himself. He thus remained unable to explore the most interesting aspect of the dilemma at hand; namely, how it feels to enjoy a lobster roll despite knowing a creature suffered in its making.

At the FrischeParadies bar, I spear gray flesh with my dainty oyster fork, then let it slip down my throat, taking care to chew as little as possible. And there it is: my gag reflex. I’ve felt it every time I’ve eaten an oyster so far (not very often). For a second, I always feel as though there’s a cold, buttered earlobe in my mouth. But the queasy moment passes by the time I’ve swallowed the last bit of brine. Oysters are a complex delicacy; that’s what makes them so irresistible.

Pleasure and Pain

Yet even if the disgust remains, enjoying an oyster may not pose an ethical problem at all; even famous utilitarian Peter Singer stated in interviews that, given the doubt surrounding their suffering, “there is no good reason for avoiding eating sustainably produced oysters.” Since, as Singer acknowledges, oysters lack a central nervous system and hardly indicate a capacity to feel pain, there is no moral imperative not to eat them. Singer’s moral philosophy revolves around the poles of pleasure and pain. As he sees it, consuming oysters is compatible with leading a good life. But can we truly be certain that oysters are insensate?

That burning question remains to be resolved. One thing is clear: These shellfish fascinate. They’re given fanciful names like Gillardeau, Tsarskaya, Utah Beach, Tia Maraa, Sylter Royal and carry an air of luxury, particularly in Germany; a luxury, moreover, that they aren’t granted at all in many other places around the globe. Paying so steeply for food that hardly satiates is truly decadent. That being said, the German palette still needs to learn to properly savor this delicacy. “Those who regard a platter of oysters without experiencing a quickening of their pulse, without beginning to salivate, have not yet discovered all of life’s true delights,” wrote Wolfram Siebeck, the German gastronome par excellence, in his Kochschule für Anspruchsvolle (Culinary School for Sophisticates). Siebeck’s book is an education in decadence. His aim: to train the German tongue, ideally through the studied consumption of French nouvelle cuisine.

Even though most of the oysters eaten in Germany originate in France, the French take a wholly different culinary tack to oyster consumption. Many street-corner stands in their country offer fantastic oysters to go for under two Euros a pop. In Mont St. Michel, there’s even a vending machine that sells oysters, as though they were candy or soda.

Intrigued, this October I found myself in a 20th-arrondissement bistro. The waiter passed me a light gray stone bowl, its surface rough to the touch. Moments before, I’d watched through the kitchen window as the cook ladled a dollop of sour yogurt cream into the bowl, placed a tartare of oysters and scallops on top, then finished the dish with a sprinkle of sorrel. How decadent, I thought: tartare, no lemon, no shells, no crushed ice. Finely diced as the oysters were—hardly distinguishable from the scallops—their taste came through clearer than ever. What do oysters taste like, exactly? Seawater that doesn’t burn on the way down. A little like fish and egg whites. A buttered earlobe.

Up in the Oyster Bar

Oysters are to be found wherever people are trying to be cool. In Johanna Dumet’s paintings, for instance. At the FrischeParadies fish counter, where author Jovana Reisinger posed in a ballgown to celebrate her book’s publication. Eating oysters has become a kind of status symbol.

The status they confer doesn’t lie in their cost, however; it’s in the knowledge required to enjoy them. Siebeck understood that when he sought to teach the Germans how to eat them. And that does require lessons: Consumers need to literally work their way in, find their way to enjoyment. The rewards to be reaped are ample; the diner’s pleasure grows with each new oyster successfully eaten.

In Berlin, eating oysters is practically synonymous with hanging out at the KaDeWe oyster bar. Beyond offering mere dining, it’s a place to take part in the performance of oyster consumption, or to simply observe others in the act. Here, on the sixth floor of the famed department store, all join in living the good life. Naturally, bestselling author Caroline Wahl met an interviewer here to discuss what it’s like to know that she’s made it. Oysters’ gray flesh is photographed, bling; emptied shells speak to excess. Even I’m taking part in this ritual, here in FrischeParadies. And I must confess: I can’t recall if I’ve ever eaten an oyster that wasn’t photographed or promptly posted on Instagram.

Perhaps, though, the crux of oyster consumption doesn’t concern status, or taste, or sustainability, or painlessness on the part of the creatures in question. Perhaps all of us—Siebeck; the established and aspiring stars of the KaDeWe oyster bar; the French; yours truly, here at the fine-dining bar in Prenzlauer Berg, in sum: all of the world’s oyster-lovers—simply hunger for violence.

Oysters present an arena where we can live out that violence without fear of condemnation. There’s something keenly aggressive about the way in which one runs the oyster knife through the meat in the shell. One quickly comes to relish the act of severing muscle from root, twisting soft flesh, killing one’s meal. Perhaps it isn’t a purely joyful rush that we feel when we repeat this ritual, time and again—it’s a violent rush, too.