Memory and Glue

Translated from the German by Julia Bosson

Editor’s note: The following text was originally presented at “Der grosse Kanton: Rise & Fall of the BRD,” which was held in Zurich on 5-6 December. It was prepared for a panel on memory culture, the history of modern violence, and new approaches in research on both.

I would like to begin with a quote from Ralf Dahrendorf, the eminent German-British sociologist and member of the House of Lords, a man who should be above suspicion of any left-wing scheming: “It is probably this blend of humanistic theory and practical inhumanity that makes Germany so unbearable at times… disrespect for the weak and defenseless… coupled with an unbounded waffle about humanism and humanity as no other country knows it.” I suspect that many people today would agree with this quote. And yet, it dates back to 1965, making it 60 years old — and it is no coincidence that it comes from Ralf Dahrendorf, a keen observer of postwar West Germany.

Ralf Dahrendorf, who grew up in a Social Democratic family, witnessed the persecution and arrest of his father and was held in a labor education camp during the last months of the war. In this respect, his biography is representative of those who critically reflected on the consequences of National Socialism after the war and also took the perspective of its victims into account. There were not many. When looking at how the former victims of persecution were treated in the postwar period, it is striking that the same dozen names keep cropping up well into the 1960s: lawyers, politicians, journalists, and functionaries — often Jewish, but not always — who, in their various capacities, advocated for the rights of survivors, for social assistance, health care, reparations, and justice. Not only had they experienced the brutality of the Nazi regime firsthand, but those who had survived the camps, such as Philipp Auerbach and Eugen Kogon, had also witnessed the suffering of those who were even more vulnerable, those who were without any public voice, even after 1945. That is why they stood up for Sinti and Roma, for former forced laborers, for homosexuals. This is not to say that this very small group was without social prejudices, but these did not prevent them from acting in solidarity. The fact remains that the only people who stood up for survivors after 1945 were themselves former victims of persecution. This must be acknowledged before addressing the topic of our “culture of remembrance.” For this reason alone, there is no cause for Germany to be proud of anything and reiterate it ad nauseam in commemorative speeches. Instead, a period of humility and reading and learning would be appropriate, in which, for example, one might engage with the memories of Nazi victims of the period after 1945, the first postwar decades. There are plenty of books and documents on this subject.

Or they lived quiet, unassuming lives, sometimes not daring to leave their homes for days because a neighbor had apparently found it amusing to park a delivery truck with the inscription “Mengele” in front of their door — the door, in this instance, belonging to a family of Auschwitz survivors.

Upon investigation, it is quickly apparent that there is much less reason for German self-enthusiasm than is ultimately allowed by the narrative of the development of a culture of remembrance against all odds, against so much resistance, for which the first four decades of the history of the Federal Republic of Germany easily appear as “fly over decades.”

But a great deal happened in those first 40 years: many former victims of persecution died in poverty, from illness, suicide, or “heartbreak,” as one nephew wrote about his aunt. Or they lived quiet, unassuming lives, sometimes not daring to leave their homes for days because a neighbor had apparently found it amusing to park a delivery truck with the inscription “Mengele” in front of their door — the door, in this instance, belonging to a family of Auschwitz survivors. So looking at these years from the perspective of the victims who survived the Nazi regime, as I recently attempted to do, a very different picture of postwar West German society emerges: It becomes clear that the core of the nationalistic sense of belonging, which was not invented under National Socialism but was exaggerated in Nazi propaganda and acted out in daily practice, remained surprisingly intact even after 1945 — despite defeat and occupation, or perhaps precisely because of them, as Hannah Arendt suspected as early as 1947. On further reflection, this is not so surprising as it initially provided Germans in the western part of the divided country with the comforting feeling that not everything had been bad or wrong in the years before. The old enemy stereotypes remained in place: anti-communism, which could oscillate between antisemitism and anti-Slavic racism, as well as everything that can be categorized under the concept of social racism — namely contempt for the “anti-social,” for the mentally ill, or for the physically disabled, as well as hatred and disgust toward homosexuals. These can’t entirely be grouped under the term “white supremacy,” because they cut much deeper into the social fabric of society and outline a much more extensive vision of inequality.

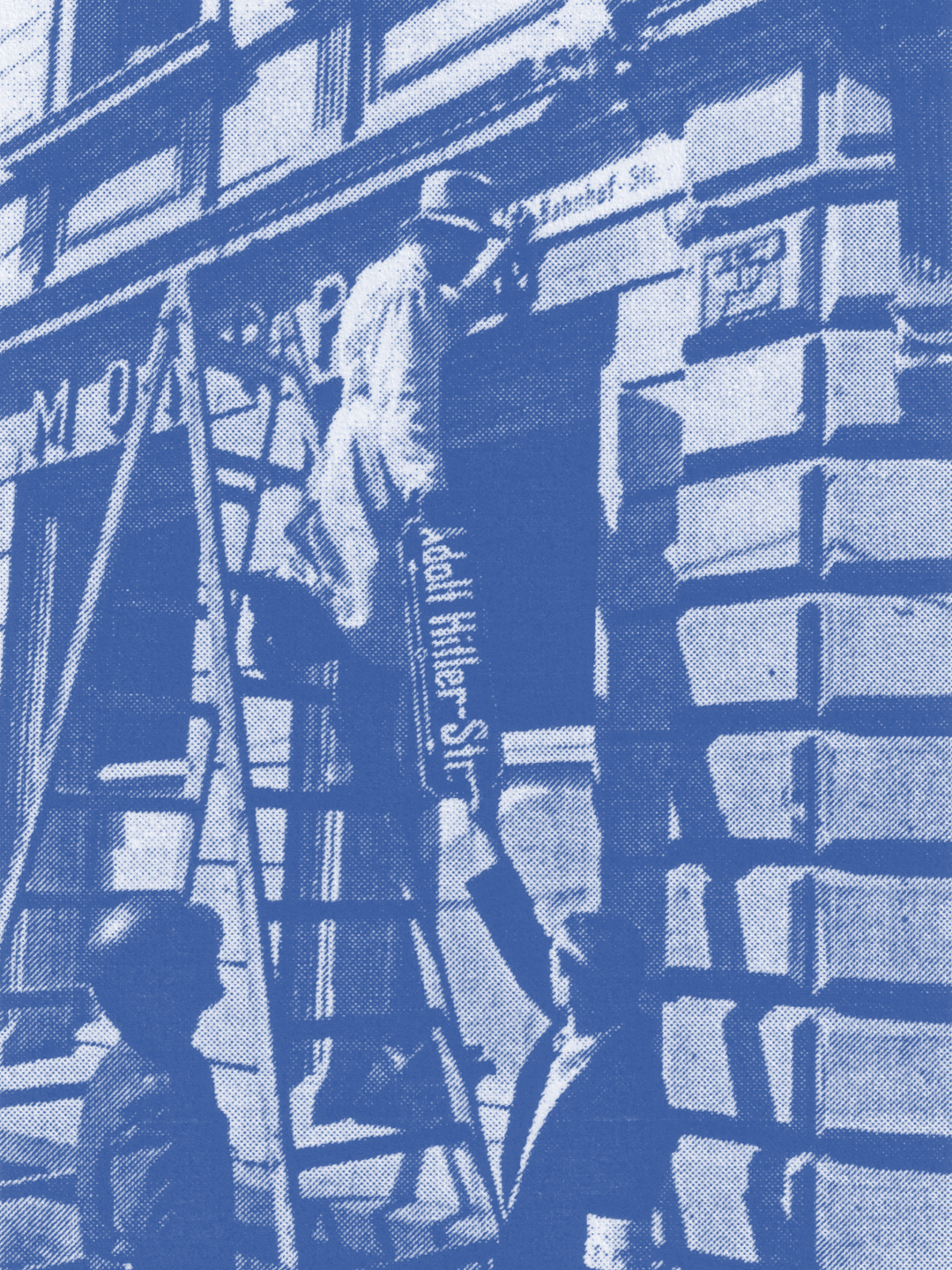

And the justification for all this was not only confirmed by mutual agreement at the Wednesday evening meet up at the local bar, but acted out daily, towards neighbors and classmates, at the housing and social welfare offices, at the police station and the immigration office, over and over again in day-to-day life. All of this is confirmed by memoirs and in a growing number of localized studies, which are full of breathtaking details unearthed from the archives. For example, the case of the “Aryanized” orchard, which was returned to a Jewish survivor who had returned to his village in northern Hesse after a lengthy legal battle. His neighbors got together and cut down all the fruit trees at night before the land could be handed over. This has a different quality than nostalgic memories of war or praise for the German autobahn. Here, aggression is running riot, and this aggression was directed against all the groups mentioned above, even if people learned over time that they had to be a little more cautious with Jews. Incidentally, the story about the “Mengele” car dates back to the 1960s.

Antisemitism and racism served, in my view, as the glue that made the transition to democracy easier for Germans, precisely because they did not have to really question their values or their national self-perception, let alone alter them.

It is important to realize that discussions of “elite continuity,” of old Nazis in ministries and courts, in the police force and at universities, is one thing: the history of the “stresses” of the “young democracy.” But these “stresses” were not only unpleasant: they had very concrete consequences for very concrete people — and lasted for decades. They also had a function: antisemitism and racism served, in my view, as the glue that made the transition to democracy easier for Germans, precisely because they did not have to really question their values or their national self-perception, let alone alter them, but they could instead reinforce them in their daily actions against the “weak and defenseless.”

The country’s ties to the West and the “economic miracle” are generally credited with the successful democratization of West Germany. The “persistence of values” in the form of a nationalistic sense of superiority is part of this. Moreover, two supporting elements, antisemitism and racism, are also embedded in the other two factors.

The “reparations payments” to Israel, which, in a sense, were a necessary contributionfor Germany’s ties to the West, were also fraught with antisemitic resentment from the outset: only 11 percent of West Germans supported this attempt to acknowledge past injustices; the vast majority, it seems, saw no need to “make amends” in this way. Time was on their side anyways, because most Nazi victims were never actually compensated as they were already dead when some payments, such as those for forced laborers, only began decades later. The link between the economic miracle and racism proved similarly lucrative: Not only were the foreign workers who were recruited as “guest workers” from the 1950s onwards assigned the heaviest, most unhealthy, and most accident-prone jobs, but the Germans seemed to remember from the 1940s that these workers could cope perfectly well with inhumane accommodation “due to their nature.” In some places, the former forced-labor barracks which were still standing became ideal for this purpose. This meant double and triple profits: low wages for the hardest work, the cheapest accommodation possible, and the desirable possibility of being able to send people “home” again in the event of accident, illness, or old age.

In short, I would like to make a modest plea to try to expand memory culture to include the postwar stories of the victims who remained in the country and their descendants. This, however, will alter the image of this country significantly, and antisemitism, racism, and social racism will become visible as continuities that continue to stabilize the structure of a German sense of superiority to this day, even if this now only refers to the automotive industry. At the same time, this focus on postwar narratives would be accessible to all young people and every family history: everyone could ask their grandparents or parents about the time, or at least identify with those who were still regulated by the 1938 Foreigners Police Ordinance1 until the 1960s. The culture of remembrance would no longer be divided between those to whom it belongs and those who have to learn it without being allowed to appropriate it. We would get a different history of the Federal Republic and a more diverse examination of a long past which, almost a hundred years later, cannot be limited to those 12 murderous years in black and white.

We could start simply by remembering the few courageous people who, even after 1945, opposed the undignified treatment of the very few survivors and thus contributed significantly to the long-term liberalization of this country over the decades — and did so under precarious circumstances: “When I leave my office, I enter hostile foreign territory,” said Fritz Bauer, attorney general of Hesse, one of the best known of these few. Today, when this liberalization is under threat, it is all the more necessary to know how it came about and the price that was paid for it.

- The Foreigners Police Ordinance (Ausländerpolizeiverordnung) of August 1938 was a Nazi era law which permitted the expelling of foreigners left stateless by their own countries, giving the state control of their residency and work permits. [↩]