Life Sentence

1.

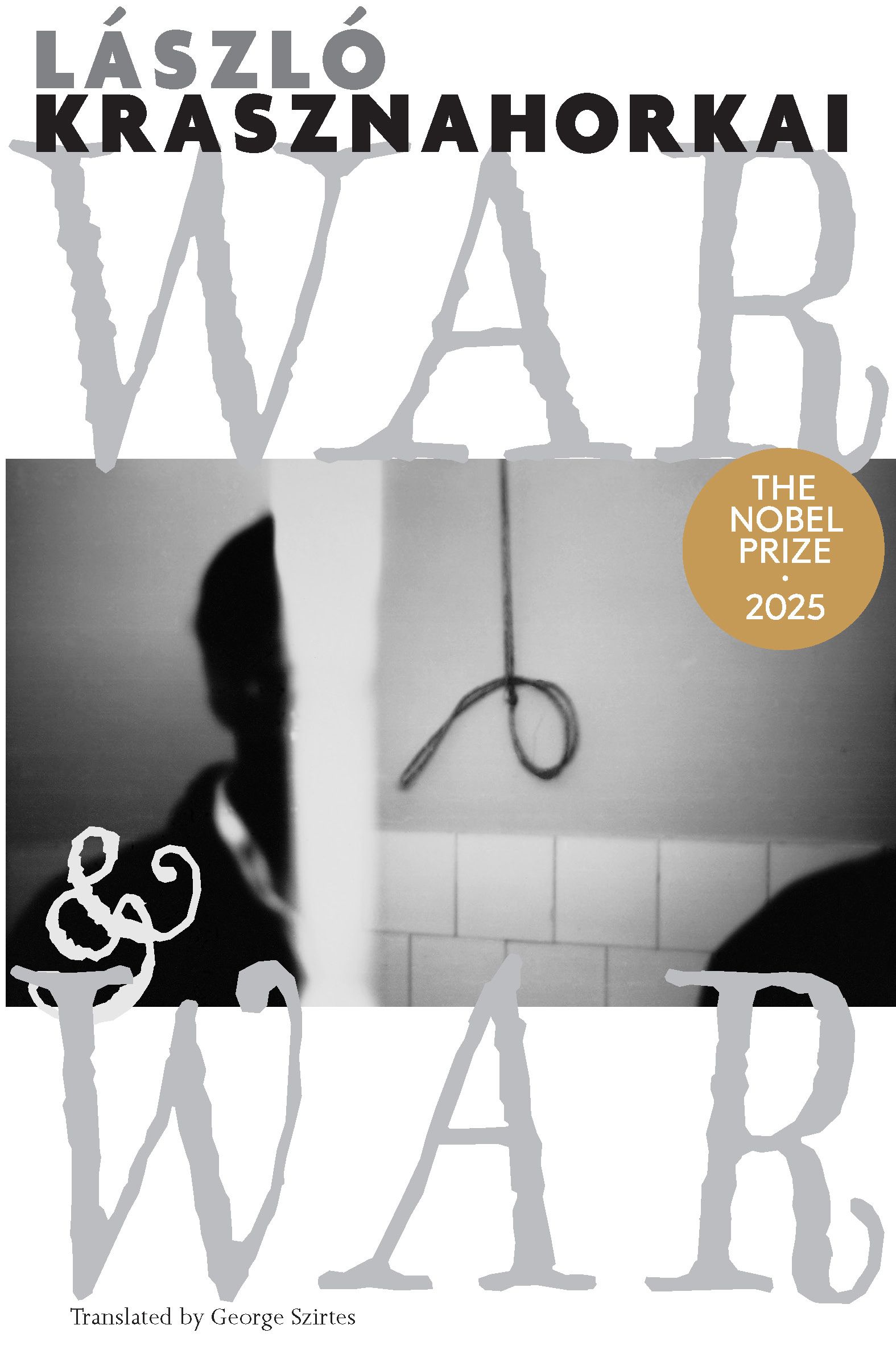

It was only when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, a prize that was founded, or so the story goes, by the inventor of dynamite after reading his own mistakenly published obituary entitled the death merchant is dead, that I discovered I had been misquoting the Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai, an author I adore, in that rather than telling the Guardian that his literary hero was Franz Kafka, he had actually said that his hero was the character K. in the work of Kafka, and that when he said “I follow him in all things,” Krasznahorkai was not paying tribute to a fellow author but rather expressing allegiance with the harried, rambling, wrongfully accused protagonist of “The Trial,” a minor deity perfectly suited to a global era that claims to have no borders or rules — no history either — but which still generates cynicism and fury among its people, offset only rarely by a kind of absurd pathetic zeal that ends in either ridiculousness or despair.

2.

Krasznahorkai writes long sentences. They run on and on and on. What drives them roaming, shuddering, lurching forward is not furious Bernhardian hauteur or camp Sebaldian vertigo but rather the author’s endless love for holy fools, for stinky incoherent visionaries, characters like Korin, star of his 1999 novel War & War, a suicidal local history clerk from small-town Hungary who chances on a historical manuscript of such beauty, such profound ambition — telling, as it does of four angelic figures who quest through mankind’s past in search of a place of lasting peace — a manuscript that he decides must be shared forever with the world before he, Korin, offs himself, a decision that drives him to New York to upload his manuscript to the internet, where this beautiful text might survive, for ever and ever, unlike Korin, who constantly gets swindled and mocked by the various practical people he meets, people whose trains of thought show us how strange and disgusting and confusing they all find him, and they are right, the joke is on Korin, he is indeed some kind of word nut and a blabbermouth, but he is somehow still the hero because the world of Krasznahorkai is a world opposed to cynics, opposed to winners, power-brokers, border guards, a world that sides every time with the lapel-grabbing loonies because those loonies’ vision — that thing they saw, which gives them hope, such stupid hope — is all that’s left to humanize us, and because they moment they stop speaking, the moment we stop listening, the moment the sentence stops, is when the haters, all those haters, win for good.

3.

László’s angels find no peace. Mr. Korin finds no peace. It is war and war, dynamite and dynamite. Before he dies, Korin uploads his manuscript to the net. You can see the text yourself at www.warandwar.com.