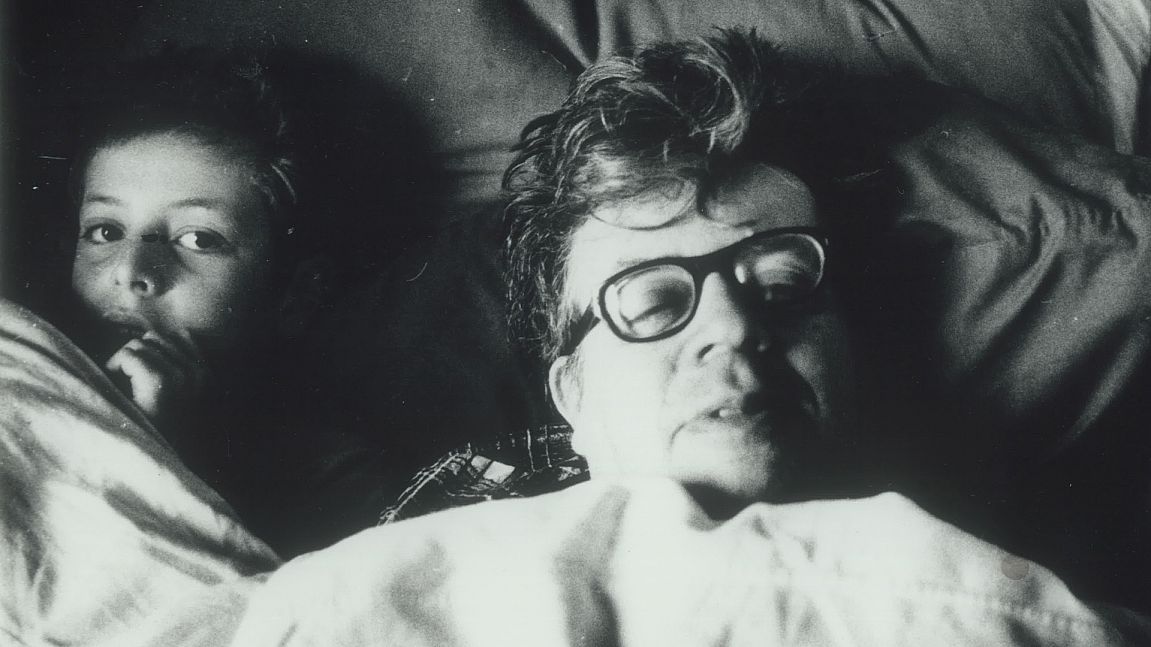

Father and Son

IT SEEMS VULGAR, to say that the Austrian-Jewish poet Erich Fried (1921-1988) had a friendship with neo-Nazi Michael Kühnen. And yet in Friendly Fire, a new documentary from Fried’s son Klaus, their correspondence approaches what Germans call a Brieffreundschaft. On such matters, the film ignites hard questions: when does political conviction give way to naivete? Can a brilliant poet believe too strongly in the magic of his pen?

Though Fried’s leftist commitments did not end with poetry — when RAF members visited London, where he lived in exile, he was happy to host — his exchanges with Kühnen evidence a belief that words can change people. Maybe they can. But as Klaus comes to realize in the film, via a conversation with RAF member Astrid Proll, his father’s neo-nazi penpal was “beyond help.”

In a Q & A, at this year’s Munich International Documentary Film Festival, Klaus, who grew up in the UK, explained that his requests to use archival footage met with resistance from nervous hagiographers. In the film he made without that material, nothing particularly disturbing comes to light, save a familiar and regrettable archetype: a man whose artistic and political drive coexisted with scotomas over the closest human needs. He travelled constantly (read: absent father).

To humanize an artistic deity is to enrich both their contribution, and our collective understanding of the join between art and life. Friendly Fire does so through surfeits of testimony and bold form. Klaus is his own leading man, rushing across Europe in search of his dad, whose anti-authoritarian and anti-zionist poems are embedded in the film’s sonic field. Co-director and editor Julia Albrecht contributed a remarkable effect: at once frantic, contemplative, and lucid. Then there’s perversely keen-eyed cameraman Ralf Ilgenfritz, who delivers Friendly Fire’s most strangely poignant segment. Ostensibly a conversation between Klaus and an acquaintance of his father’s, the scene is really a pretext for an intimate encounter with Austrian meat. For what feels like half an hour, we listen to Klaus and his counterpart talk. The latter debones a juicy hunk of beef, upon which Ilgenfritz dotes an almost worrying amount of attention.

The sequence is overdetermined but not overcooked. Something other than meat is clearly being processed, be it memory, the baffling tissue father-son relations, or the no less perplexing question of what German verse is and could be, and be for, now. It’s not easy to know why this little carnivorous spectacle works so well. But it does. That’s poetry.