Eyes Wide Shut

A Turkish diva in the land of Hitler and Beethoven

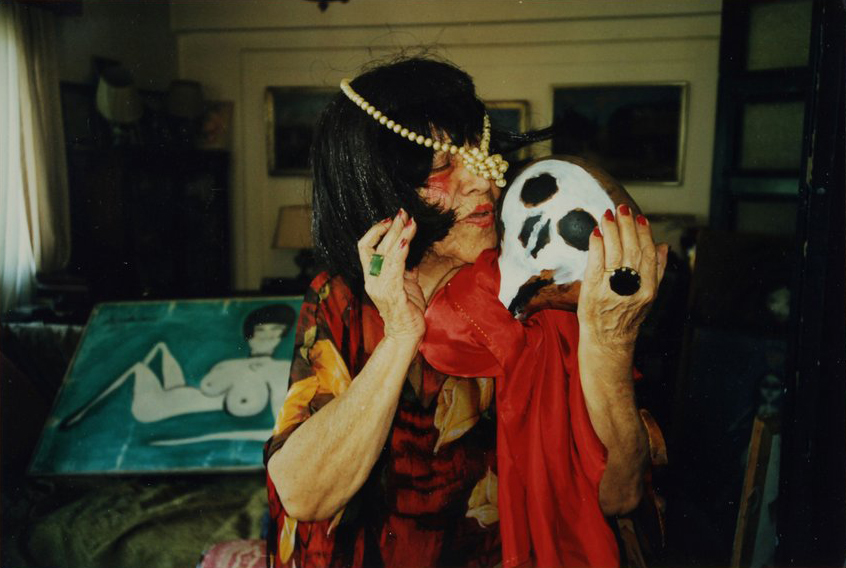

THE FIRST TIME SOMEONE stepped into Semiha Berksoy’s Istanbul home, they might have noticed her refrigerator. Nearly every inch of the appliance was painted on — as was every other available surface in her house. Berksoy painted wherever she could, as if the boundaries between life and art didn’t exist.

Semiha Berksoy was Turkey’s first internationally recognized opera singer, allegedly the first Turkish woman to perform in Europe, and a pioneering artist whose surreal, haunting self-portraits set her apart from easy categorization. She was extravagant, larger than life, known for dressing entirely in pink and for blending opera and visual art — she once created a kinetic painting, “La Tosca’nın Temsili,” where the figure’s arms could move, echoing her own 1941 Ankara performance as Floria Tosca.

I hadn’t heard of Berksoy before walking into Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, where a 2025 retrospective, spanning six decades of her artistic career and running until May 11, shed some light on her life’s work (as well as her fridge). “Semiha Berksoy. Singing in Full Colour” traces her connection to Berlin, where she studied music in the 1930s, and showcases Berksoy’s deep ties to the cultural landscapes of Turkey, her home, and Germany, where she often returned. But the more time I spent in Hamburger Bahnhof, the more I noticed what wasn’t there. The exhibition makes the case that her time in Germany shaped her professionally, where she built social connections and found influences that lasted her whole life. But what about the political circumstances of her time? How did a woman who lived in Nazi Germany engage — or not engage — with the regime? What was being left out?

The Face of a New Republic

To understand Berksoy, you have to start with the Republic that celebrated her. By the time Berksoy was 13 years old, in 1923, the Ottoman Empire was gone, and a new nation, the Republic of Turkey, was emerging — one eager to position itself as modern, secular, and European-facing. This was a country that saw art, and especially opera, as a tool of transformation, and women onstage as symbols of progress. Berksoy was swept up in that project, becoming the first Turkish woman to receive state funding to study opera in Berlin.

She was, in many ways, the poster child for the Republic’s ambitions: educated, worldly, talented. Semiha Berksoy’s artistic journey began in 1928 when she studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts before expanding her training to ceramics and sculpture. But her ambitions were never confined to visual arts. Through Muhsin Ertuğrul, the influential director of Istanbul City Theaters — who himself moved between Turkey and Berlin’s film industry — Berksoy stepped onto the stage. In 1934, she was cast as the lead role of Ayşim in Özsoy, Turkey’s inaugural opera, commissioned by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who personally attended its premiere.

Before she left for Berlin, Hikmet wrote to her in 1936, reminding her of the world she was stepping into: “May your path be open; not Hitler’s land, but Beethoven’s homeland; I wish you victories that are not bloodstained, but full of life.”

Her paintings tell a different story: They are not sleek, nationalistic celebrations of “progress,” but deeply personal, surreal, chaotic. She painted herself, over and over again, in various states of being — sometimes defiant, sometimes devastated, often alone. The body is raw and exposed, the colors violent, the compositions unsettling. Her canvases — often masonite panels or fabric sheets — featured self-portraits, her signature rouged cheeks staring back, alongside depictions of other family members and her artistic influences. She treated her paintings not as commodities but as vessels, surrounding herself with them and gifting them to friends, believing they carried the spirits of those she loved. If the Turkish Republic wanted to use her as proof of its success, it would have to contend with the fact that her art refused to play along.

Berksoy moved in elite intellectual and artistic circles, forming deep friendships with major cultural figures, most notably, with Nâzım Hikmet. Her relationship with Hikmet was part romance, part artistic dialogue, part friend supporting friend. The revolutionary poet and committed communist was imprisoned for over a decade for his anti-state writings before being exiled to the Soviet Union and stripped of his Turkish citizenship. Berksoy, meanwhile, starred in operas commissioned by that very state. She moved in the orbit of political struggle. And yet, her art rarely reflected it. Was she deliberately avoiding ideology – or simply absorbed by her own vision? Before she left for Berlin, Hikmet wrote to her in 1936, reminding her of the world she was stepping into: “May your path be open; not Hitler’s land, but Beethoven’s homeland; I wish you victories that are not bloodstained, but full of life.”

The Berlin Years

Berksoy arrived in Berlin in 1936, one of the many young Turks sent abroad under the Republic’s modernization project. The idea was simple: Send students to Europe to acquire knowledge and skills, then bring them back to build the “new Turkey.” Berksoy, already a promising opera singer, was expected to return and take the stage at the Istanbul City Theater.

And in Berlin, she thrived — at least on the surface. Turkish students in Berlin lived well. They immersed themselves in the city’s cultural scene, frequenting opera houses and theaters. Their scholarships were generous, their status respected. The Nazi government, enforcing its racial policies, had banned Jewish landlords from renting to Germans, so many Turks found themselves living in prime real estate, often in upscale Jewish-owned apartments around Kurfürstendamm. Photographs of Berksoy from that time — wrapped in a fur coat, wearing a slightly tilted stylish hat — tell a story of comfort and privilege.

Berskoy was admitted to the Hochschule für Musik by Paul Lohmann, a German vocal coach who had spent time in Turkey, helping to establish a music program in Ankara, where she had auditioned for him. She also performed in Berlin, though not in the way history might like to remember. In 1939, she sang in a student production of Ariadne auf Naxos, as part of a series of events celebrating the 75th birthday of its composer, Richard Strauss. Though she earned praise for her voice, there is no evidence that she ever performed on one of Berlin’s major opera stages, and a rejection letter confirms that she had applied to work as an unpaid extra in the Prussian State Theater’s chorus.

While the doors of high culture remained largely closed to her, the production of Ariadne auf Naxos placed Berksoy in the orbit of an important figure: Hanns Niedecken-Gebhard, a theater director best known for staging the opening ceremony of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, one of the most infamous displays of Nazi propaganda. Niedecken-Gebhard later worked with Berksoy’s classmates at the Hochschule für Musik, supporting the stage direction in Ariadne auf Naxos. Even in a student performance — especially one that took place in Nazi Germany — politics was never far from the stage.

Among the Nazis?

Berksoy’s time in Berlin wasn’t just about music; it was about relationships, social circles, and moments of intimacy that would shape her life. Berksoy met Elisabeth Schwarzkopf at the Hochschule, the German British opera singer who was one of the leading sopranos of her time — and a member of the NSDAP. She also wrote to Fritz Schäfer, who had met Berksoy in 1938 and began to write to her repeatedly, even after all Turkish students had to leave Germany as a result of the war breaking out in 1939. His letters reveal an unsettling detail: when they first met, Schäfer was a member of the SA, the Nazi paramilitary organization. Later, Schäfer himself joined the Luftwaffe. In one letter that gives further insight into what kind of conversations Berksoy was having at that time, Schäfer makes mention of her assumption that German soldiers wouldn’t be allowed to dance with foreign women, to which he didn’t agree. In fact, he wanted to see her again.

Berksoy did not see Berlin as a city of persecution – she saw it as unfinished business, a place where she had once studied and where she wanted to belong again, where she wanted to continue her art.

In one letter from 1941, addressed to an unnamed professor, Berksoy sends birthday greetings and expresses her wish to come back to Berlin, despite the war. Another from 1944 offers confirmation of Berksoy’s time spent at the Hochschule, written by her professor Paul Lohmann. The document was officially notarized in Turkey, but alongside the Turkish stamp is another — the eagle and swastika insignia of Nazi Germany. These weren’t just symbols. They were everyday reminders that Berksoy had studied in an institution operating under full Nazi control. In her application, she would have seen questions for “members of the Jewish race only.” Some professors signed their letters with “Heil Hitler.” She wasn’t unaware.

Yet in 1942, while World War II was still raging across Europe, Berksoy made her way back to Berlin to visit friends, hoping to resume her studies — without any luck. By then, the Final Solution was in motion. Millions had already been displaced, deported, or killed by the Nazis. But Berksoy, it seems, did not see Berlin as a city of persecution — she saw it as unfinished business, a place where she had once studied and where she wanted to belong again, where she wanted to continue her art.

Lost to History

Yet none of this is front and center at the exhibition. When I set out to uncover Semiha Berksoy’s politics, I had hoped to find something the official record left out, something that indicated how this woman who lived through so much history responded to it. However, for a woman whose voice once filled opera houses, her silence echoes just as loudly in the space she left behind. And the retrospective at Hamburger Bahnhof –– along with descriptions of her in the Turkish press –– presents her as avant garde and timeless, as someone occupied with her own artistic practice, her paintings structured like operatic vignettes, drawing visitors into the theatrical world she built for herself.

But I’m not sure that’s the whole story.

Perhaps Berksoy’s work represents escapism, maybe the dreamy self-mythologizing was a desire to rise above the politics of the time. Or she took the moral weight of simply existing in that time and place and made it work for her. She was, after all, a woman surrounded by ideology — by men in uniform, by shifting power structures, by a world that was actively purging people from its ranks.

Berksoy was born into one of the most politically charged eras in both Turkey and Germany. She was celebrated as an opera star, used by Turkey to prove that the country had “arrived” on the world stage, that a modern Turkish woman could “make it” in Europe. In the West, specifically in Germany, it was primarily through her paintings that she gained recognition. She kept coming back, visiting music festivals and appearing on talk shows, but only ever as an eccentric artist, the woman who lived in her own theatrical universe, as if the world outside and the politics she lived through had never touched her. As if she had lived in Germany’s darkest era without being scarred by it.

To me, I think the absence might be intentional: Hikmet told her she was not stepping into Hitler’s land, but Beethoven’s — and she took that to heart, deliberately turning away from politics and seeking “only” the arts.

It’s that absence, that refusal to engage, that unsettles me now. Without it, we are left grasping, trying to pull apart which of her actions were taken out of conviction, out of opportunity, out of friendship, out of ambition, or out of that same impulse to see the world and expand her horizons that many young women share. She enjoyed being the first, the best, and seemingly, that was enough for her. No guiding political ethos, no public reckoning with the forces that made her singular in the first place. We have her self-portraits, but we will never know what she saw in Nazi Germany. Or what she chose to look away from.