Westwards, Through Air

Translated from the Hebrew by the author

In Tamar Raphael’s short story Westwards Through Air, Danielle, the narrator, has recently moved from Tel Aviv to Berlin alongside her partner, Daniel, where she is enrolled in German class, taught by a woman named Daniela. The names are only one of a series of mirrors and slippages in the text: between student and teacher, German and Hebrew, door and mirror, I and you.

Danielle’s journey reflects a sociological reality: Berlin is home to a sizable population of leftwing Israelis who have sought refuge in the city over the years. Raphael’s writing reflects this engagement, playing between harsh political truths and Danielle’s own bourgeois and ironic sensibilities. This story, told in sentences that wind between past and present, interiority and observation, is about listening and failing to listen, about speaking and failing to speak.

Raphael’s first novel, There Were Two With Nothing To Do, which offered a window into leftist social groups in Tel Aviv, was released in Hebrew in 2024 to much acclaim. Westwards, Through Air is the first translation of this writer’s fiction into English and German.

— The Editors

The apartment we left in central Tel Aviv in June of 2022 was a pale imitation of the one we had been forced to leave a year earlier in Jaffa, and the apartment we found in Berlin was a ruin compared to either, but still we counted ourselves lucky because we had found an apartment in Berlin. “Very nice,” I said after the miserable results of the November elections, when people started talking about leaving the country. “We beat the traffic.” We could say we had seen it coming, and it might even sound plausible — at least on Daniel’s part. The truth is, if we hadn’t been kicked out of that place in Jaffa, we never would have left. Around the time when our landlord in Jaffa called us from her fancy rehab facility in Miami and told us she was selling the apartment to French investors and therefore kicking us out, I was working in a newspaper’s photo archive, and instead of doing my job — an endless indexing of photos of masked pedestrians passing by shuttered restaurants — I spent my days staring at photos from the 2005 Gaza disengagement1 and sending them to friends in WhatsApp groups: Photos of women crying, women clutching at other women, women clinging to the remnants of their homes, women held by soldiers, their bodies nearly springing forward from the soldiers’ restraining grasp. I sent those photos to my friends and wrote “Yup, that’s me,” because I could no longer ask for pity after days of seeking it, but I could ask for a laughing emoji, and I could get one, and for that I had to mock myself, and I wanted to mock myself, because I knew which people in this land were really evicted from their homes, cruelly and without reason — and those were not the settlers from Gush Katif nor were they us. We never had the right to claim a tragedy of our own on this land, least of all in Jaffa — even if it was north Jaffa, even if it was the edge of Jaffa — and yet when we lost that apartment I cried as if my world had come crashing down, just as the evacuees from Gush Katif did, and we all dismissed them then and dismiss them still and always will. From our bedroom in Jaffa, you could see a bit of the sea and an enormous palm tree standing in the courtyard. You could see some crooked, broken rooftops — a view I wouldn’t have recognized as a view if it hadn’t been sung about in all those songs I’d listened to hundreds of times. A cloudy rooftop above the city, the plaster crumbling; under the sagging ceiling, a small room. Those lyrics once made me imagine a life that always looked like that — hunched, dingy, and celebrated in song — and I thought I’d seek that life at the edges of the world when I grew up, but I never had the courage to go that far. From the living room that faced east, you could see a boulevard, its trees enormous too — not palm trees, maybe sycamores; I say that cautiously because I don’t know anything about trees, but I think they were old, fat, very green sycamores. Less green were the treetops of the boulevard seen from the window of the next apartment in central Tel Aviv. Looking for a new place after having been kicked out, we faced a reality check. The reality, as the city’s real estate agents kept saying, was that the world had turned upside down. Forget everything you know about life, they said: Jaffa is now more expensive than central Tel Aviv. And so, even at a better price, the imitation had to be pale. From the bedroom window we could no longer see the sea. From the living room window we saw a boulevard with sycamores, but they weren’t fat, weren’t old, weren’t green. If only they had been a bit greener, I might have persuaded Daniel that his academic potential did not justify uprooting us to Berlin, and we wouldn’t have ended up in this apartment in Neukölln, which is now our home, where in order to glimpse a patch of sky you must lean half your body out the window and risk breaking your neck. The entire first winter in Berlin I kept saying I only wanted to speak one clear and meaningful sentence, but in truth, I also wanted a beautiful apartment with a view of the canal, where sometimes, in summer, a ray of light could slip in — because in this apartment the UVB lamp stayed on even in summer — and a year later, Daniel left me alone in the darkness when he flew to Los Angeles for an entire month to visit a research institute that had filled him with false hopes by overestimating his academic potential — false hopes that would soon be dashed, and the first side effect of their collapse was a total change in what I could and could not say to Daniel, his transformation into yet another person who took offense easily in a world full of people who take offense easily, this after years of being completely immune to insult, which I had taken advantage of. “You sure enjoy making fun of me in front of people,” he’d say. “Lucky for you I’m such a good sport.” And more than once I would reply that he was lucky to be who he was, and I was lucky to be with who he was; meaning he was one hundred percent lucky, and I was fifty percent lucky, so I was just trying to make the most out of my luck, which was effectively his. However, in the end, even that luck was subject to change and it ran out after Daniel realized that he would never be a professor, and that we had left Tel Aviv for nothing. We left the apartment in Tel Aviv with its not-quite-green-enough treetops outside the windows for nothing, and for nothing we moved to a city without charm and an apartment without a view, always dark. Into that darkness I would return from the Hebrew classes I taught at the adult education center not far from Rosenthaler Platz, in an area where as a tourist I used to shop for clothes and look at contemporary art, and from that darkness I would leave each morning into the sunshine for the German classes I attended at the language school across from the Warschauer Bridge. As a tourist, I thought there was a certain appeal to the Warschauer Bridge, because I came to it only with the intention of singing with others, at night, singing with friends and strangers at the karaoke bar, drinking gin and tonics and singing for hours, devouring ’90s pop hits with everyone, slipping an obscure song into the list so that no one would join me and the stage would be all mine, then watching everyone exit the booth to buy more gin and tonics, leaving me alone to choke on the unfamiliar song. That’s what I did when I went to the area around the Warschauer Bridge as a tourist. I didn’t notice that the bridge was actually frightening; I didn’t notice that addicts fell asleep standing on it. Only as a registered resident, only as a German student who returned there every morning during the summer of 2022 did I notice that this was a place where reality appeared fully ripe, almost rotten, and I tried to pretend I was indifferent as I crossed the bridge, that I couldn’t tell gold from rust, that my home wasn’t a refuge from the ugly face of Warschauer Bridge but simply the place where I did my work — the work assigned to me — to be who I was, to be a person with my luck, which was the luck assigned to me, and was neither more nor less deserved than the luck assigned to the homeless man whose chin rested on the railing and whose eyes were closed, and if he moved for a moment out of his stupor, if he dreamed that someone was chasing him, he might fall onto the train tracks, just as a train was arriving at the station where I disembarked every morning to reach the school at the far end of the bridge, between the karaoke club and a large candy shop. There, I was a migrant among migrants. All of us had enough money to pay for language classes and enough time to dedicate three hours a day to them. Other aspects of our luck and fate were set aside; we were vessels for vocabulary and grammatical structures that were stacked one upon the other within us, and we had to hold them as if they were a tower of plates we were asked to balance and carry through the city’s streets, and never let them break — but it was unclear when, or whether, we would ever be able to lay them on a table and eat from them. The teacher’s name was Daniela, and she looked a lot like me. If I had fed her photo and then mine into an app that shows which celebrities you look like, it would surely have returned the same list of actresses no one has heard of. You could almost mistake us for one another — if not for the fact that she was from Bavaria and I was from Tel Aviv, as I used to tell my students instead of saying I was from Israel. Daniela didn’t say she was from Bavaria, but in the first lesson I discreetly asked ChatGPT under the table: “Where in Germany do they have a rolled R?” and it answered: “In Bavaria.” Later I asked ChatGPT what stereotypes there are about Bavarians. I asked whether Bavarians, according to stereotype, hate being corrected. I asked whether there was any group in the world for which such a stereotype existed. According to ChatGPT, there isn’t. And yet Daniela’s offense when I corrected her in the lesson was so obvious that the whole class turned their backs on me for several days, and to me that felt ungrateful because I hadn’t corrected her for my sake, but for theirs. I knew that an infinitive was a universal term, that even the intricate system of German grammar could not rob it of its meaning. I knew that because of the identical forms of the infinitive and the plural present tense, Daniela was extrapolating a separate infinitive from the plural Präteritum form — and I knew that this was leading an entire class astray, setting a trap not only for her students but for herself as well, because I knew the price a confused teacher pays for a confused class, but the other students didn’t know that. Neither did Lin, who sat next to me for two full weeks, during which I began to like the scent of the oil she dabbed on her wrist several times during every class. But Lin also shunned me after I corrected Daniela. After two whole weeks by my side, she moved to another seat. “You moved seats,” I said when I entered the classroom, and she replied, “Yes, sometimes you have to change places to change your luck. In Arabic we have a proverb like that.” Just a few days earlier, she had told me she admired Neturei Karta2. I thought I misheard and asked her to repeat, and she explained impatiently that there was a man named Neturei Karta whom she watches on YouTube, and as a neo-traditional Muslim she finds his spiritual path inspiring. “A man named Neturei Karta?” I asked, and she replied that he was the leader of a very important spiritual group, and scolded me: “You’re from Israel and you’ve never heard of Neturei Karta?” I should have told Lin that by my calculations I’d known about Neturei Karta when she was still in her crib and her family was boarding a flight from Damascus to Doha at the start of the drought, if she had ever heard of the drought — but “Neturei Karta” isn’t a person’s name. I didn’t say that because Lin wasn’t the teacher, and I had no one to protect from her mistake. I just asked if she was sure that was a person’s name. “He’s so charismatic and interesting,” she said. I still have no idea whom she was talking about. Later she offered me fruit, the next class too, and again, until I corrected Daniela, and then she moved to a different seat and no one spoke to me until Muhammad joined our class — not just in the middle of a semester, but also late on his very first day. Because he was late, Muhammad was instructed to quickly state his name and where he came from, no further details, and we weren’t given time to ask him follow-up questions as was customary when a new student joined. We all lifted our eyes from our exercise books and I heard him say: “Muhammad, Palestine.” Daniela said, “Great, so now we have two Pakistanis in the class,” because that was Daniela: anxious and harried to the point of not listening. She would often say Genau when a student was wrong and Leider nicht when one was right. Besides, the distinction between Palestine and Pakistan didn’t carry the same charge for her as it did for me or for Muhammad. “Do you know each other?” she asked Muhammad and Rama, the actual Pakistani student, pointing at them both, and I was stunned at Muhammad’s politeness when he didn’t correct her. He and Rama just looked at each other and both said, “No.” I was pleased by the presence of Muhammad because he was tall and handsome and wore a crisp white Muji button-down shirt and glasses with shiny acetate tortoiseshell frames. Daniel’s long trip was already on the horizon, and in the presence of a tall, handsome, well-dressed, intense-looking man, it was easier for me to imagine the space and time opening up and other elements aligning into the conditions of possibility of cheating on Daniel. For Muhammad, I would have changed my seat in class. I planned to approach him at the break, extend my hand, and say, “Nice to meet you, I’m from occupied Palestine” — as if I didn’t usually dismiss that phrasing as virtue signaling, as posturing, as sycophancy. I planned to ask Muhammad why he hadn’t corrected Daniela, why he hadn’t said, “Not Pakistan, Palestine.” I planned to laugh with him about Daniela, recruit him to my side, warn him about her, encourage him to correct her next time, as there surely would be a next time. During the break I ate a bag of marshmallows from the big candy store next to the language school and the karaoke club, because that morning I had again forgotten, as always, about what was to come — about lunchtime — and hadn’t bought a packaged salad from the supermarket. I sat with my marshmallows in the corridor, on an uncomfortable chair, instead of eating in the empty classroom as I usually did, so that Muhammad would see me when he returned from his smoke break. And so he did. As he came back from the smoking corner, he passed through the corridor. I looked at him and he looked at me. He said, “Enjoy your meal.” I said, “Thank you.” I took out a marshmallow from the bag and offered it to him. He declined with a barely perceptible gesture but kept standing next to me, and I didn’t have the courage to say what I had planned to say. I didn’t say, “Nice to meet you, I’m from occupied Palestine.” Instead, I said, “I think I didn’t hear right earlier. Where are you from?”

“I’m from Pakistan,” he answered. “And you?”

Not out of courage, not for his sake, nor for the sake of those who had said it before me, nor for Palestine — but out of defeat and a desire for defeat — I said I was from occupied Palestine. And he looked confused. He looked shaken. He looked as if he had a lot to say about every aspect of the topic, but all he did was ask — in German, suddenly, even though we had spoken in English until then — whether I knew Adi.

“I know many Adis,” I replied in German, and he asked, again in German, “Many Adis?” and I didn’t have time to answer because Daniela shut the door because class was starting. That was her way — always shutting the door even if we were right next to her. She never said “Come in.” If she had said “Come in,” as I used to say to my students ten seconds before the end of every break, we would certainly have said, “Just a moment, please,” just as my students always said to me. But instead, she closed the door, and we would feel insulted, and out of a sense of injury we would walk up to the closed door and open it. That day I resolved to try out Daniela’s technique in my own class, and so I wound up insulting my dear student Bianca, a literary critic who had moved to Berlin from Friuli, Italy, and refused to tell the class why, who was comfortable in German and was now learning to be uncomfortable in Hebrew, greatly enjoying when new students joined our Hebrew class every month so she could ask, in simpler syntax, why anyone would do such a thing to themselves. Bianca was flushed when she opened the door, right after I had slammed it upon seeing her limping slightly toward the classroom. She asked if I was blind, if I hadn’t seen her coming, and if I knew that she had undergone a cardiac catheterization earlier that week — which I didn’t know — but I burst into tears as I tried to apologize for slamming the door in her face, and Bianca said in Hebrew, “It’s okay,” and then added, Quando si chiude una porta, si apre un portone. For the rest of the lesson I let the students practice among themselves because every time I tried to teach something new, I felt a great wave of tears rising again. Only after they had acted out entire dialogues — doctor and patient, vendor and customer, police officer and thief — did I feel some relief. I clapped my hands and corrected their mistakes in a clear voice, but when I said “See you on Monday,” the great wave of tears rose again, and I couldn’t stop it. My students left the classroom with heads bowed as I wiped the board and my tears, and only Bianca came up to hug me and said in Hebrew, “It’s okay, I know I didn’t mean to hurt you,” and said she had once written something about that, without explaining what she meant, and asked about my German. “It’s improving,” I said, and she hugged me again — and that was the first time it occurred to me to try reading her literary criticism. The essays written by Bianca, which I discovered online and read alternating between German and machine translation, had in recent years been directed at the narcissism rampant in literature, and all of them resting on the same underlying assumption: that there is necessarily a barrier between writer and reader, that a hierarchy necessarily exists in which the writer is the master and the reader the slave. When Bianca read the word “I” in a book, she translated it, I feared, to “you,” resisting the first-person narrator’s invitation to identify with them. Upon reading lines like “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they executed the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York. I’m stupid about executions,” she automatically read: “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they executed the Rosenbergs, and YOU didn’t know what YOU were doing in New York, Esther. YOU are stupid about executions.” This was as clear to me as day, though I was neither a linguist nor a renowned literary critic, because I was a Hebrew teacher — and, as it happened, Bianca’s Hebrew teacher — and I knew well the prevalence of confusion between “I” and “you” in the beginning levels, which Bianca was still susceptible to. In the first class of every A1.1 Hebrew course, when everyone stands stripped of their adulthood, confused, they must learn by imitation the dialogue — “Shalom, who are you?” “I am X. Who are you?” “I am Y.” — and recite it in pairs. The teacher plays both roles in two different voices, with the help of pictures or puppets, and then begins to drip-feed it into their open mouths. In the first round of student participation, the teacher must still play the role of Y. After waving like an idiot while saying “Shalom” and miming puzzlement at “Who?” she points at a selected student when saying “You,” and in fifty percent of cases, like an idiot in turn, the student repeats the pronoun “you” instead of replacing it with “I” and attaching their name to it. They say “You are Hans” instead of “I’m Hans,” and how does one begin to argue with that? “No, no, Hans! I’m Danielle, YOU ARE Hans.” “You are Hans,” they will say again half the time. “No, no—I—I—I’m Danielle. And you are?” During this recurring nightmare, which happened once every semester, I flourished. I sensed the torture and flourished. I could already smell the chocolate candies I would receive at the end of A1.2 level — the level where the true pedagogical miracle occurs. Before level A1.1, they couldn’t read a single letter of the Hebrew alphabet. After A1.1, they are able to say a few words they would have learned after one lesson in any Romance or Germanic language — but alongside them, an entire script for which they have zero use, except perhaps to sound out the words of Finnegans Wake in Hebrew and fail to understand it like everyone else in every other language regardless of fluency. Much of the practice in these classes involves deciphering the phonetics of meaningless chains of syllables — so why not:

bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk?

They never admit they’re frustrated, but throughout A1.1 level, they are— and it’s up to me to hold their hope, as they say, that one day this will all mean something. By the end of A1.2, those who had faith finally see the letters form complete sentences. Then they gift you with a box of chocolates. But after the chocolates comes the A1.3 ingratitude — the plateau. They stop recognizing the importance of new vocabulary, whose selection now seems arbitrary to them. They’ll always want to know how to say something that was excluded from the syllabus and will stubbornly forget the words that were included in it — chosen actively, if not meticulously. Within this obstinate forgetfulness, even the mastery over pronouns will erode and regress. The plateau will sometimes transform into regression. The difficulty of switching between first and second person in dialogue will once again stand between the students and the teacher, who already knows she won’t be receiving any chocolate at the end of this semester. Every time a student omits the pronoun altogether and asks, for example, “Where do live?” the teacher will remind them of the missing word, and the student will repeat it when they should have switched between first and second person, and switch it when they should have just repeated it. In the practice of question words, pronouns will become a total morass:

– He lives in Jaffa. What’s the question?

– Where does he live?

– Fantastic. We are going to the lake. What’s the question?

– Where are we going?

– Sorry, you’re not going to the lake. We are. What’s the question?

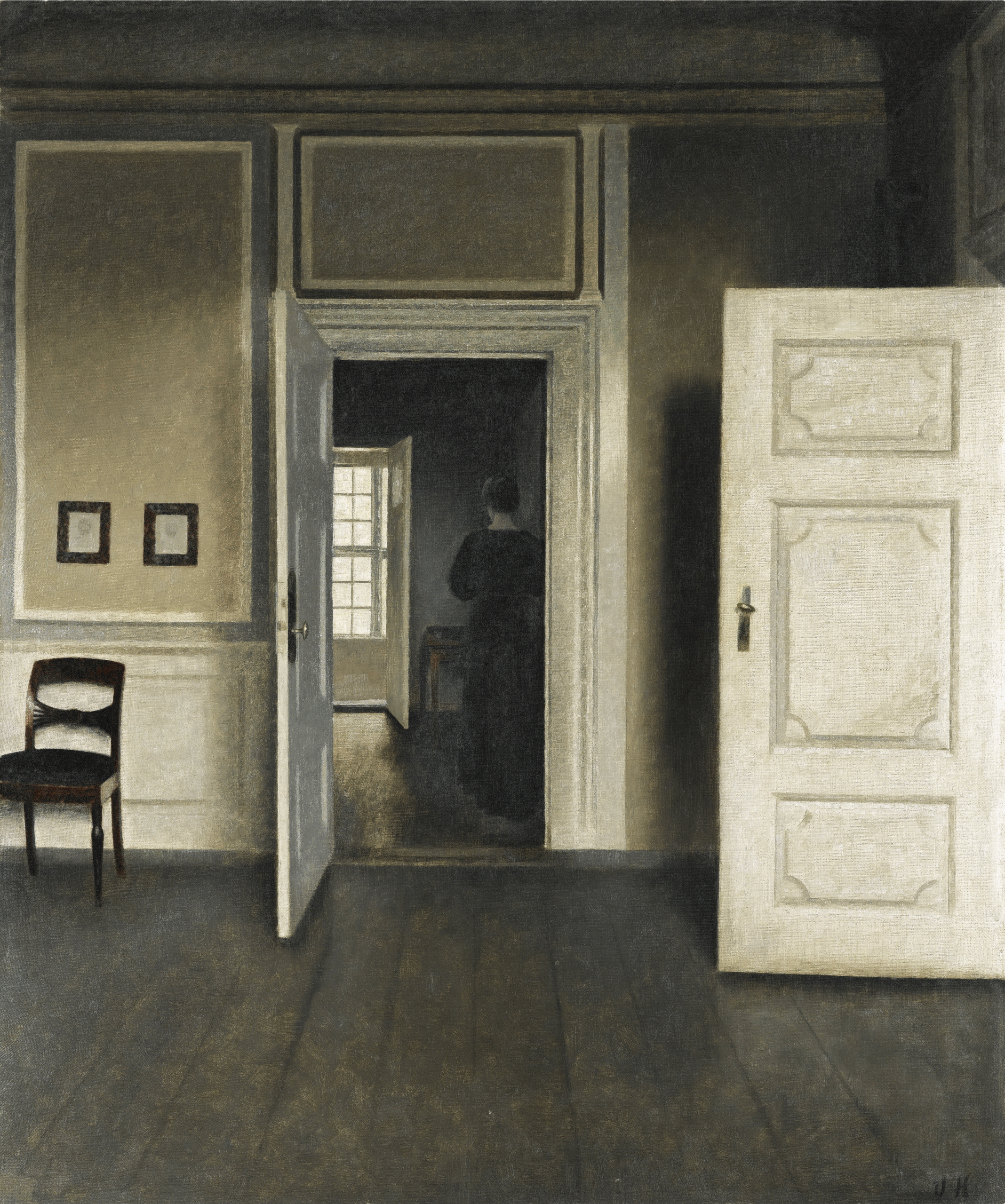

The teacher can content herself with the student knowing the answer — i.e., knowing the question word — even if they show indifference to the pronoun, even if it’s clear that pronouns still do not ignite in them the experience of self and other, the experience of self and present other, self and absent other, the experience of quantity or the experience of gender. But Bianca, the renowned literary critic, was not like that. She knew her A1.3 Hebrew very well — so much so that I sometimes suspected she wasn’t advancing to the next level simply because she didn’t want to part from me — and until I slammed the door in her face, she never had difficulty switching pronouns in dialogue. I suspected, however, that she did switch them unnecessarily when reading literature in the first person. Like many other cultural critics, her writing lamented the fact that young people today think they must see themselves reflected in every work of art. They read a book and expect it to be a mirror, whereas a book should not be a mirror but a door. When I followed Bianca’s ideas to obscure forums and YouTube clips, I saw a young Canadian author quoting her and clarifying, summing up, in German — to an unclear audience — Nie ein Spiegel, immer eine Tür, or “Never a mirror, always a door,” as my German was strong enough to decipher. For a moment I was surprised, since among this young Canadian author’s books was indeed a memoir about her decision not to become a mother which somehow resulted in becoming a mother, and many of its passages were written in the second person, yet she had also written a wonderful novel with dystopian undertones, and it was obvious that she was a serious reader of dystopian literature, and, in general, a broad reader, unafraid of unfamiliar knowledge, unfamiliar realities, or unfamiliar fictions — and therefore, despite the memoir, it was obvious that she preferred doors. It was only several days later, crouched in the bathroom stall at the German school across from the Warschauer Bridge, hiding because I’d heard Muhammad’s voice in the hallway say ‘Hey, Adi,’ and the voice of someone who was presumably Adi answer, ‘Hey, you!’, only then I realized that I had missed the main point in Bianca’s remarks because I had been too busy thinking about kinds of texts instead of kinds of readings. The Canadian author wasn’t saying she preferred one kind of books, but that she preferred to read them in a “door mode” rather than a “mirror mode.” That is: whether we are reading about what is most distant from us or about our twin sibling — who can also be the most distant from us — we should seek the other, the unfamiliar, rather than the reflection of ourselves. My student Bianca probably wanted to shout her door mode from every rooftop as a counterreaction to the prevailing mirror mode — but she tried to demonstrate that it was literature itself that had become unusually narcissistic, instead of arguing that narcissism was flourishing around it, in its margins, among its readers. This was proof that the door mode could itself become a bit harsh and invite a proliferation of “I walked into the door” type accidents — which, as we know, are always lies, as something else always happened. Is there any point, I asked myself, cutting class, riding the S-Bahn and then the U-Bahn, then half-breaking my neck to look at the sky from our dark apartment in Neukölln, in reading an intimate first-person text purely as an anthropological report? The question of style I set aside, because even though Bianca knew how to appreciate poetic qualities, she cut straight through them to get to the content, and if the content was infected, in her view, with the disease that was spreading through literature, she did not succumb to the temptation: she would replace every “I” with “you,” as if it were impossible that the one who keeps saying “I” might be saying something true about her too — and thus, from the start, hadn’t been talking about themselves at all but about her, and she couldn’t see that. I asked myself whether, when we read a first-person text, we are not obliged to convert every pronoun into all the other pronouns simultaneously, as if we were all very patient students of languages who had reached the plateau.

- In 2005, Israel carried out the unilateral “Gaza disengagement” (Hitnatkut) under Prime Minister Ariel Sharon. Approximately 8,000 settlers were evacuated from 21 settlements in the Gaza Strip and four in the northern West Bank; the Israeli army permanently withdrew from Gaza and emptied out its bases. [↩]

- Neturei Karta – A small, ultra-Orthodox Jewish sect that rejects Zionism on theological grounds, viewing the establishment of a Jewish state before the coming of the Messiah as a violation of divine will. Although they oppose Israel’s existence, their strict religious fundamentalism and rejection of secular modernity distances them from left-wing or secular forms of anti-Zionism. [↩]