The Green Drop

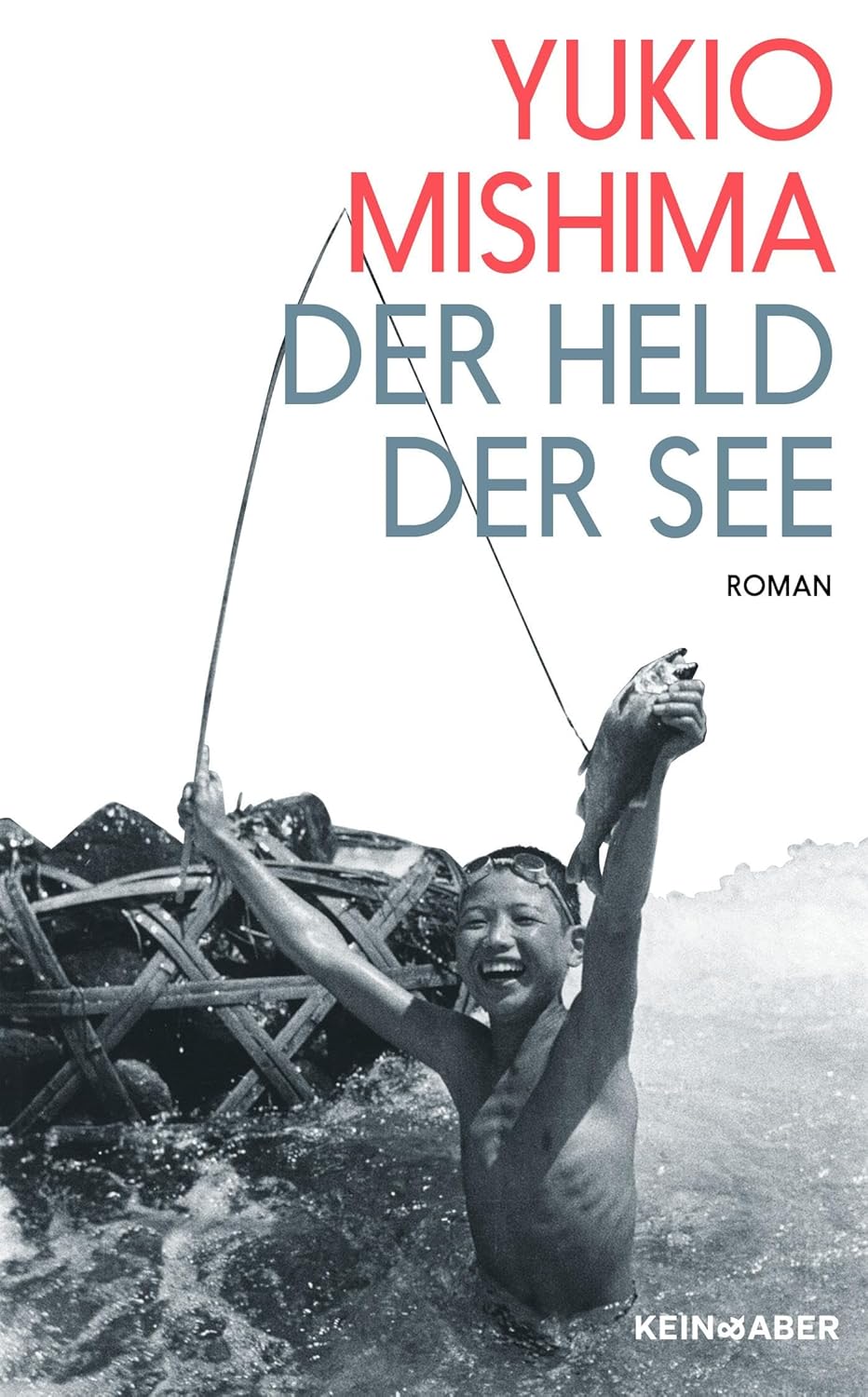

I don’t believe that books can really give us hope. What they can do, though, without a doubt, is shake us to our very core. My last such experience took place two weeks ago, courtesy of Yukio Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (1963), released in a new German translation by Ursula Gräfe.

The novel opens with an unforgettable scene that plumbs the psychological depths of childhood, of desire, and of repressed cravings: young Noboru, who has grown up without a father, has taken to watching his mother through a peephole in the closet between their rooms. When she brings home a new lover, a sailor, the boy witnesses the scene that becomes as embedded in his mind as ours. In the evening light, the two adults undress and stand naked in front of each other when “suddenly the full long wail of a ship’s horn surged through the open window,” the sailor turns to the window “with a sharp twist” and looks out to sea.

The novel’s entire drama is contained in this double glance – the forbidden gaze of the child toward his naked mother and her lover, and the gaze of the sailor away from his naked lover out to sea. It leads to a tragedy so terrible that even Mishima does not spell it out.

It was not the sight of the forbidden realm of nudity and sex that was so unsettling to the child’s eyes, but the witnessing that there can be something greater than sex: here, the earthly, ultimately dirty and banal eroticism; there the call of the sea.

Mishima himself is said to have suggested the title of the novel to his English translator. As we know, the loss of grace has always been the ultimate punishment – reserved for traitors. And the sailor Ryuji commits a betrayal in the eyes of Noboru when he begins a new life on land to marry Noboru’s mother. Has the child’s sense of disappointment in dreams ever been more magnificently expressed?

“Naturally, Noburu stuck close to Ryuji during the holiday and listened to sea stories by the hour, gaining a knowledge of sailing none of the others could match. What he wanted, though, was not that knowledge but the green drop the sailor would leave behind when some day, in the very middle of the story, he started up in agitation and soared out to sea again. The phantoms of the sea and ships and ocean voyages existed only in that glistening green drop.”

The green drop that is left behind: this book is such a drop. Rarely has a book glistened so much.