If You Don’t Want to Talk About Racism, Keep Your Mouth Shut

Translated by Julia Bosson

I’ve read that Friedrich Merz has brought down “the firewall,” the Brandmauer. Hundreds of thousands have taken to the streets in recent weeks, holding signs, and chanting about resistance, cohesion, the need to protect democracy. But what is this storied monument known as the Brandmauer all about? When my mother came to Germany in 1980, the term Brandmauer did not exist in everyday politics, but there were former NSDAP members in German parliaments.

The metaphor first appeared in the political rhetoric of the late 1990s. I don’t know where it came from or why, in the debate about distancing the right, it has gained so much significance one might think it has always been there. How I see it, postwar German mythology was formed on the basis of a host of charged words. These terms are supposed to describe and define German identity after National Socialism: words that promise change, such as Erinnerungskultur (culture of remembrance), Einwanderungsland (immigration country), and Multikulti (multiculturalism) — but also words that seek to codify an authoritarian status quo, such as Leitkultur, or misappropriated terms like Staatsraison, which have gone from the realm of foreign policy to an instrument used in social debate — or used to prevent debate.

I have internalized some of these words (those from the left-wing, anti-fascist spectrum); they have formed me politically and made me become active, out of the perhaps naive belief that something really can change in this country if we only make an honest effort, if we really fight for social and political participation and a good life for everyone. Today, I have considerable doubts about this “we,” as I have noticed more often in recent years that there are walls that actively exclude people like me from negotiating who belongs here and who is allowed to help shape it.

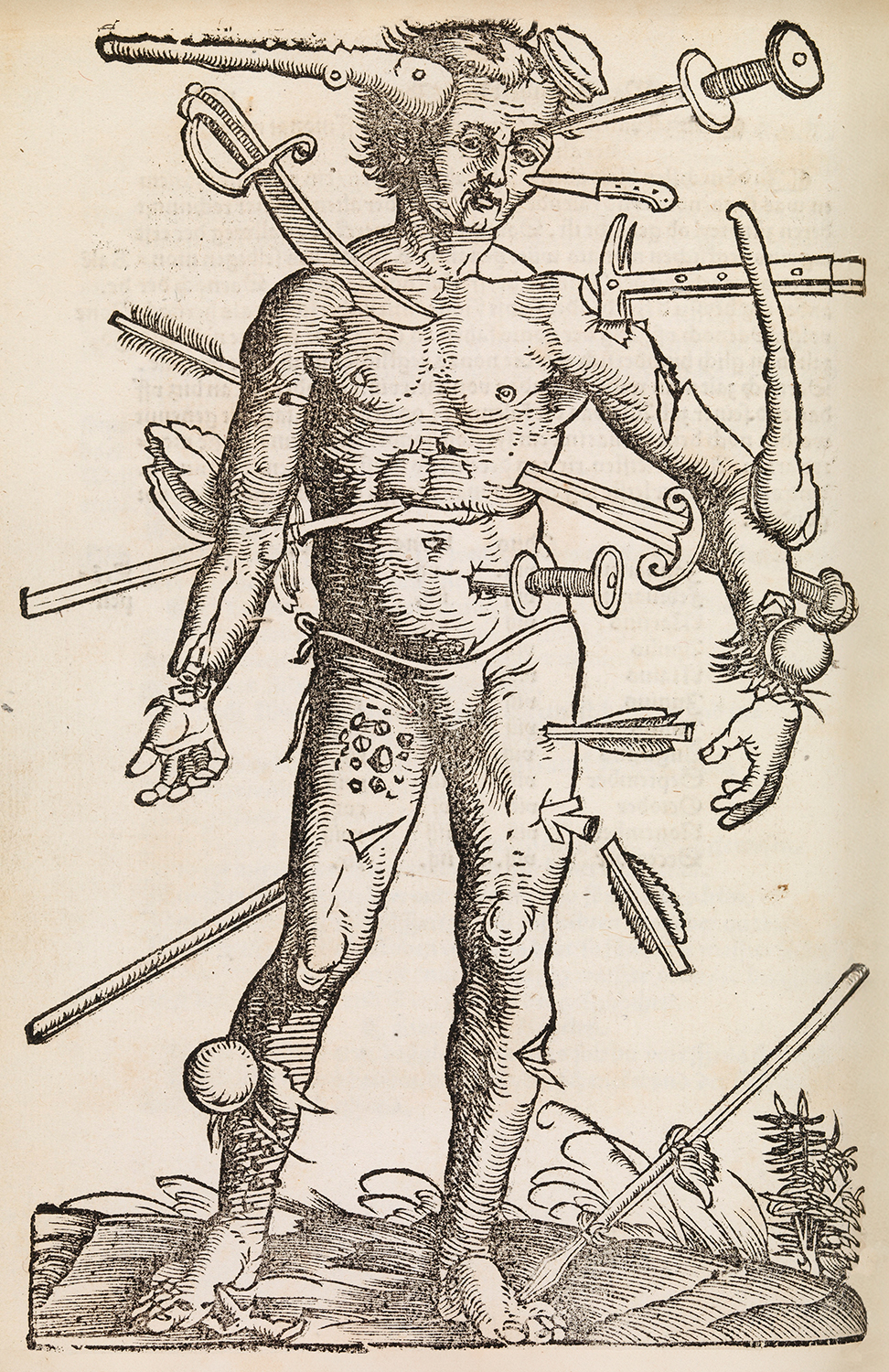

So if I, as a Black German — a contradiction in terms of the German self-image, because apparently a German passport is not enough — am to take a position on the Brandmauer, then at most I can state that there is no room for me on either side of it. The Brandmauer was unable to protect any of the people who died in asylum shelters set on fire by Germans in the 1990s. Nor did it protect Oury Jalloh, who was murdered by the police when he burned to death in a prison cell in Dessau 25 years ago.

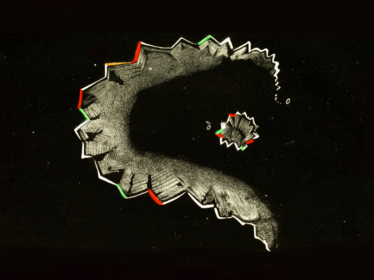

The accelerant comes in the form of debates over refugees, asylum compromises, and deportation initiatives: If you don’t want to burn, it’s better not to come here in the first place

In Germany, the response to violence against racialized people is even more violence. The accelerant comes in the form of debates about refugee, asylum compromises, and deportation initiatives: If you don’t want to burn, it’s better not to come here in the first place. When benevolent Germans clapped at train stations in 2015 during the refugee crisis, many of us “foreigners” secretly suspected that the less benevolent would clap even louder ten years later when we “went home again.”

2025 marks the 5th anniversary of the right-wing extremist terrorist attack in Hanau. Incidentally, firewalls do not protect against bullets. Neither could they protect the victims of Hanau, nor Mouhamed Dramé, Lamin Touray, Christy Schwundeck, and numerous others who were shot dead by right-wing extremists, the NSU, or the police. Who are “we” for this democracy, apart from the others? The debates in politics and the media about how to better protect those affected by racism have failed to materialize, while for their — our — communities in this country, things have been on fire for years.

The fundamental problem — that deeply-rooted institutional racism in Germany corrupts and destroys the democratic process from the outset — is consistently concealed. At the same time, it can be strikingly observed again these days that racism as a political force is the gateway to fascism. If you don’t want to talk about racism, you should also keep quiet about democracy.

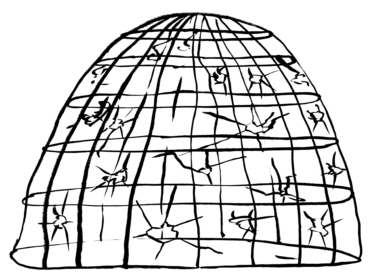

Here, they build mass accommodation that easily catches fire, but certainly not firewalls.

A country whose politics are becoming more and more fascist, whose racism is becoming more and more carceral1 and is being cast in more and more resolutions (and soon probably also laws). A country that refuses with all its might to come to terms with its own racist colonial, genocidal past, a past in direct continuity with the horrific Nazi genocides that followed. A country that would instead prefer to expel those from universities who point out this connection. A country that uses a romanticized version of its own history as an excuse to ban people from speaking their language, restrict their freedom of expression and assembly, and beat them down. A country that allows the growing number of Nazi demonstrations in the east to march unchallenged; a country that prefers to talk about German security rather than our security; and a country that, in a democratic election, is by a staggering majority willing to hand the government over to those who boast of being able to launch the most deportation flights: One such country is Germany. Here, they build mass accommodation that easily catches fire, but certainly not firewalls.

- Operating according to the logic of prisons and police, increasingly defined by borders and camps in the wake of neoliberal structural change in recent decades. State-sanctioned violence criminalizes and punishes in particular those who are considered “superfluous,” “useless,” and killable (“surplus populations,” Ruth Wilson Gilmore) by the system for the mere fact of their existence. [↩]