From Auschwitz to Skyscrapers

A few years ago, on a long rail journey across Germany, I decided to stop in Frankfurt to look at the city where my grandparents once lived. My Berlin-born grandfather escaped Nazi Germany as a child but returned to Frankfurt in the 1980s as an Israeli envoy, experiencing a mixture of attraction and revulsion towards the country that had expelled him and attempted to murder his family. I inherited this relationship to Germany from him, along with his stinginess. Before I got into Frankfurt, I booked a room in the cheapest hostel in town. It was a perfect location, I thought, only a few blocks away from the train station.

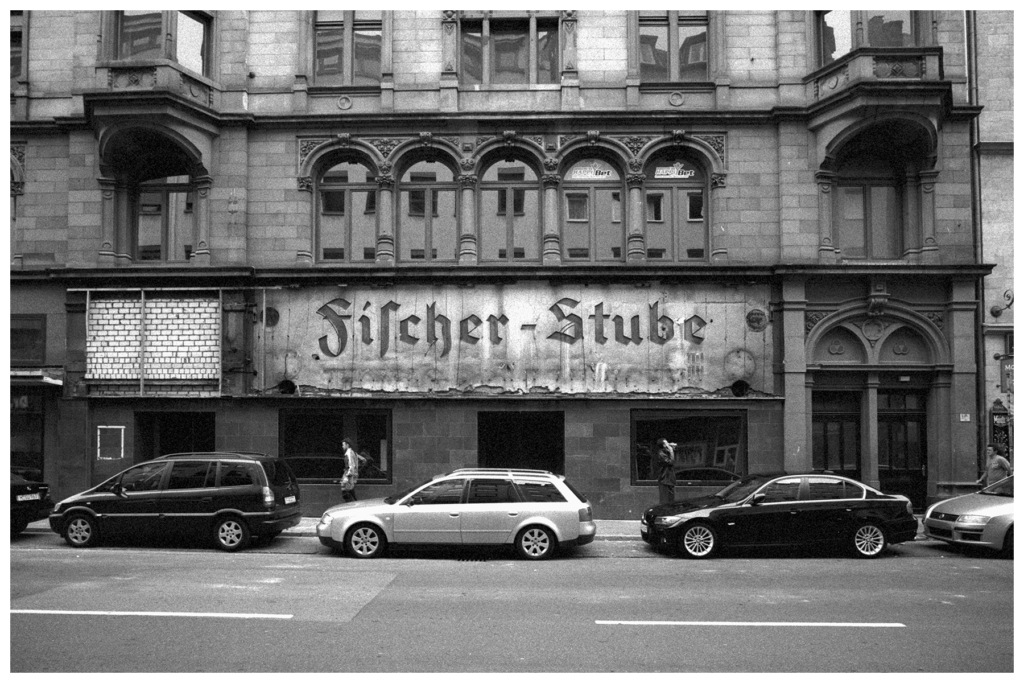

Upon my arrival, I discovered that most of the rooms were rented by the hour. The hostel turned out to be a brothel, and Frankfurt’s Bahnhofsviertel (train station quarter) — the German capital of crack. The dirty streets of the red-light district scared me, but not as much as the dirty sheets in my drugged-out room. I could not fall asleep, and at night, I wandered. Next to a methadone clinic, I was surprised to see a sign in Yiddish, for a jewelry store.

This group of Polish Holocaust survivors amassed fortunes that rose to tremendous heights through shady business dealings, and were labeled by some German journalists as a mafia.

I didn’t know it then, but I had stumbled upon a trace of the Jewish ganefs of Frankfurt (this word, originating from Yiddish, means crooks or petty thieves). This group of Polish Holocaust survivors amassed fortunes that rose to tremendous heights through shady business dealings, and were labeled by some German journalists as a mafia. I cannot speak to the extent of illegal activity among the ganefs’ deeds, but several years of research and a master’s thesis later, I can attest to their impact: Elusive yet omnipresent, the few dozen ganefs lie in hiding behind almost every important Jewish moment in the Federal Republic’s history. From strip clubs to trade in stolen bedsheets, they are the glue that bound “the Jews” to post-war Germany.

The chronology of the ganefs includes many twists, from organizing riots in German courts in the 1950s, to entertaining American GIs in the 1960s, to the biggest diamond robbery in Israel in the 1970s. Their lasting legacy, evident in contemporary German-Jewish culture, echoes broader themes of diasporic “mafias,” stretching from the Sicilians and Jews of New York to migrant communities in today’s Germany.

As in many such cases, the marginalized Jewish survivors of Frankfurt have turned their outcast status into a commercial advantage. The goods given to them in aid packages were turned into a tradable commodity, and their social ostracization enabled them to develop a sort of autonomy. And as elsewhere too, their relative freedom, originally exercised in the hidden corners of society, eventually influenced high politics, affecting diplomatic and legal relationships between Germany and Israel. But despite the many side plots in their story, the ganefs’ basic trajectory is rather clear: from the concentration camps to the black market outside Frankfurt, from there to Frankfurt’s clubs, and on to real estate. Let us start, as they did, in Zeilsheim.

Cigarettes, Chocolates, Sometimes Even Coffee

Most of the Jews of Zeilsheim, the Displaced Persons (DP) camp in the suburbs of Frankfurt, were originally from Poland. After liberation, many survivors attempted to return to their hometowns, looking for relatives and hoping to rejoin their communities. However, the ferocity of post-war antisemitism in Poland — where 42 Jews were murdered in the 1946 Kielce pogrom — made it clear they were still unwelcome. Impoverished and traumatized, many fled westwards, to the American sector in Germany. In an ironic twist, it was safer for Jews among the Germans who had just tried to exterminate them than in their Eastern European hometowns. Some of them ended up in Zeilsheim.

The camp in Zeilsheim had a turbulent cultural life, with a newspaper, synagogue, theater, competing political parties, a massive baby boom — and a flourishing black market. The survivors owned virtually nothing — no clothes and no money, which had virtually no value in the post-war devastation anyway. But the DPs received parcels from various aid organizations, packages full of luxuries that the Germans could not obtain: cigarettes, chocolates, sometimes even coffee. The DPs started dealing in these supplies, establishing a huge black market at the gates of the camp that attracted both Germans and American GIs. In the words of survivor and historian Arno Lustiger, “We didn’t go hungry, we were given food, but we did not have any everyday objects. You had to get all that somehow, organize it, ideally by exchanging food or cigarettes […] everything on the black market, there was nothing in the stores.”

Research by the historians Michael Berkowitz and Kierra Crago-Schneider has shown that Germans channeled their post-war antisemitism into criticism of Jewish participation in the black market: Just a year after the fall of National Socialism, the former Nazis restricted themselves to calling the Polish-Jewish refugees criminals. In actuality, the impoverished DPs’ trade was dwarfed by Germans’ involvement in illegal trade. It is therefore right, perhaps, that the few Jews who actually became major black market profiteers were spared public scrutiny. Yet they did become the stuff of cultural legend.

The Entertainment Sector

The Frankfurt gang used fake IDs of their murdered friends to get extra food rations, they dealt in counterfeit money, and they swindled Germans with old rags, pretending they were high-quality bed sheets. These practices were documented in many films and books, such as Irene Dische’s reportage about a bar mitzvah where all the ganefs gathered and Michel Bergmann’s books about illicit bedsheet traders, one of which was also turned into a film. There was also plentiful reporting in Israeli media indicating that these DPs, who smuggled goods behind the Iron Curtain and sold counterfeit watches in Frankfurt’s main train station, were certainly not the passive, fearful survivors that post-war narratives make them out to be.

The gang first made it into the news with a violent act against one of its own members: Auschwitz survivor Josef Buchmann, not even 20 at the time, was put on trial in 1951 together with four friends for stabbing another Jewish survivor, who had apparently tried to run away from Frankfurt with a suitcase full of money. According to an article from the 1960s, Buchmann, who wound up as one of the most successful members of the gang, avoided prison only because another friend of his, Erwin, took the fall. According to one source I interviewed as part of my research, Buchmann rewarded Erwin generously, financing him until his death and even paying for his gravestone.

Jewish crime was tolerated by the Germans, who turned a blind eye to people with numbers on their arms.

By the 1950s, with the liquidation of the DP camps and the emigration of almost all Jewish DPs from Germany to Israel or the U.S., the Zeilsheim crew, composed of young, male, and secular Polish camp survivors, moved downtown and began to enter the entertainment sector, opening bars that offered a different kind of pleasure. Maxim Biller described their new fields of activity in the story Wenn ich einmal reich und tot bin (“Someday When I’m Rich and Dead”), through the character of Amichai Süßman, who “brought the train station district under his control very quickly right after the war” and “because he did not know any better, he brought his organization under the same rules as he had learned in Treblinka: it started with a strict hierarchy, with the most meticulous work and delivery deadlines for his girls and middlemen, and ended with the rigorous chastisement and punishment of anyone who refused, was too weak, or wanted to get in his way.”

Although the sensational Israeli press — which always revealed more about the Jewish underworld in Germany than its more cautious German counterpart — explicitly wrote that some of the bars that the ganefs own were in fact brothels, the ganefs usually denied it. Buchmann himself even took his case to court in 1954 when a semi-pornographic U.S. GI newspaper hinted that his New York City Bar was in fact a grand brothel and a center of organized crime. Buchmann also ordered his people to attack the photojournalists who tried to capture him during his court appearance, breaking the equipment of one and the bones of the other. Buchmann won the cases: The Overseas Weekly’s circulation was stopped, and the photographer who took his picture without permission had to pay him compensation.

Jewish crime was tolerated by the Germans, who turned a blind eye to people with numbers on their arms. The Americans also favored the ex-victims over the ex-perpetrators, and were the main patrons of the Jewish bars. But not only Americans visited the more than 50 Jewish-owned peep-show clubs in Frankfurt and its surroundings. According to my interviewees, they were also frequented by Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor W. Adorno. In their reporting, Israeli journalists noted how shameful it was that most of Frankfurt’s seediest Lokals — as the clubs were called — were owned by Jews. But according to the Zionist narrative of the time, the biggest disgrace of these camp survivors was not their criminal lifestyle, but rather their decision to continue living in Germany at all.

These Israeli crooks — most of whom were neither of German nor Polish origin — were the first Israeli group to break the taboo of migrating to Germany.

By the 1970s, the criminal activities of Jews in Frankfurt had only expanded. Articles from the time reported the growing activity of Israeli drug traffickers, who initially came to Germany to work as shlegers (Yiddish for thugs) for the Polish Jews. When Shimon “Kushi” Rimon was caught amid a heroin transaction, the Israeli was kept in jail alongside members of the far-left underground RAF and former Nazi officials. After several legendary escape attempts, which included setting the prison on fire, the Germans extradited Rimon to Israel.

These Israeli crooks — most of whom were neither of German nor Polish origin — were the first Israeli group to break the taboo of migrating to Germany. Perhaps it was easier for them than for others, because simply living in Germany was still regarded by many Jews as practically criminal. In some ways, my grandparents, who came to Frankfurt as representatives of a respected Israeli company a decade later, were following in their footsteps. And having moved to Berlin three years ago, I guess I have too.

Kosher Real-Estate

In the mid-1960s, Buchmann gave up his two most famous bars, the Imperial and New York City Bar, the latter of which had 40 women stripping every night. Buchmann invested his wealth in what would mark the start of a new chapter in the ganefs’ trajectory: real estate. Buchmann financed Frankfurt’s Shell-Hochhaus, the first skyscraper in a city that would become known for its skyline. He also helped to push old residents out of the Westend neighborhood in order to make space for the new developments. This step represented a lessening dependency of Frankfurt’s Jewish businessmen on the occupying Americans, formerly their patrons and protectors, and an attempt to move to more legitimate domains.

The Westend squatters have already been the subject of a whole literature, their fight against the neighborhood’s destruction becoming the most significant leftist cause in post-1968 Frankfurt. The activists argued that the rich landowners were using criminal methods to kick residents out — like staging robberies or intentionally neglecting properties — yet they also overemphasized the Jewishness of some of the landlords, playing on and reinforcing antisemitic tropes.

The Westend riots inspired a controversial play by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Der Müll, die Stadt und der Tod (“Garbage, the City, and Death”). In it, a character called “The Rich Jew” is a real-estate mogul with a penchant for whores, an object of open resentment. As one character puts it: “He sucks us dry, the Jew. Drinks our blood and blames us, because he is a Jew and we are to blame. […] And the Jew is to blame, because he blames us, because he is there. […] They forgot to gas him.” In German, it almost rhymes.

The play’s 1985 premiere in Frankfurt, three years after Fassbinder’s death, made headlines. A group of Jews, including survivors, sat onstage, protesting the play’s alleged antisemitism, and prevented the show.

It was then that the Jews of Frankfurt stepped out of the shadows, literally occupying the main stage, and began to vocally advocate for their own perceived interests.

Today, when there are once again widespread attempts to cancel leftist artists over accusations of antisemitism, the discussions of that time are more relevant than ever. Defenders of the play, including the Jewish leftist squatter Daniel Cohn-Bendit, argued that Fassbinder’s work was in fact a critique of lingering German post-war antisemitism rather than an endorsement of it. Fassbinder himself had made similar comments before his death, though many did not believe him.

However, there was one point on which everyone agreed: The protest against the play became a pivotal moment in German-Jewish history. Even Cohn-Bendit regarded it as the “coming out” moment of Jews in Germany, and the protest against the play was widely regarded as the first time the Jewish community in West Germany engaged in public political action.

It was then that the Jews of Frankfurt stepped out of the shadows, literally occupying the main stage, and began to vocally advocate for their own perceived interests. The declarations and press conferences that followed had a significant impact on the role of the then Frankfurt-based Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland (the Central Council of Jews in Germany), transforming it into the prominent and engaged political entity we see today.

The Fassbinder controversy and its fictionalized ganef laid the foundation for contemporary German-Jewish politics. But much has changed since that watershed moment: In contrast to the present, the demand to cancel Fassbinder’s play originated from the Jewish community itself, with the protestors rioting against Germany’s cultural institutions rather than being supported by them. Additionally, the Jewish community’s demand was based on the needs of the Jewish community in Germany, and had nothing to do with the actions or interest of Jewish people elsewhere.

He is still alive, and in fact, this illiterate orphan who grew up in a concentration camp is now one of the richest people in Frankfurt.

This was not the last milestone marked by a ganef scandal. Another was the 1990s’s so-called Beker affair, when the ZDF documentary Mafia am Main labeled Buchmann as the “godfather” of Frankfurt. The film accused two other Polish Jews (the Beker brothers) of trafficking women and leading a massive corruption scheme involving many city officials and the planned renovation of the Bahnhofsviertel, eliciting public uproar. One of the Bekers, Hersch, fled a hospital stay and flew to Israel, where his lawyer argued that Germany’s investigation was antisemitic. Although Hersch Beker pleaded not to be sent to trial in the country that once tried to exterminate him, this line of defense did not work. He became the first Jewish person to be extradited from Israel to Germany, marking the improving relations between the two states following German reunification.

The Bekers were ultimately acquitted, as was Buchmann. He is still alive, and in fact, this illiterate orphan who grew up in a concentration camp is now one of the richest people in Frankfurt. He is also a major benefactor of Frankfurt University and Tel Aviv University—the godfather of the academic partnership between the two cities, if nothing else. Today, law students at Tel Aviv University attend their classes in the Buchmann building.

Unpacking Myths, Unpacking Suitcases

Since my visit to Frankfurt, I’ve conducted interviews with people who begged me not to quote them and went to as many archives as you can count on both hands, yet my research is barely halfway through. I keep finding more and more moments in history with the ganefs’ fingerprints all over them. This group played a role in improving German-Israeli relations, bringing the first Israelis to Germany and provoking the first extradition to Germany. The gang provided not only shikses (non-Jewish girls) to American GIs, but khayune (livelihood) to Oskar Schindler, who actually lived off their plate for a while, long before Steven Spielberg made him world famous. A play about them mobilized the Jewish community in Germany to take the spotlight, and they left an unmistakable mark not only on Frankfurt’s red-light districts, but on its now-iconic skyline.

The recent German series Die Zweiflers, a family drama about Frankfurt Jews that received many positive reviews, presents the ganefs through the character of Symcha, the grandpa. In the first episode, his grandson evokes the brothel he once owned and burned for insurance money; the press describes him in the series as a person with connections to the underworld, with “bars, red-lights, illegal casinos and a murder that remains unsolved to this day”; and his family justifies him being a Jewish criminal in post-war antisemitic Germany, representative of the ganefs’ logic.

I have analyzed the use of Yiddish in Die Zweiflers, and as I have argued there and in an interview, the series does a wonderful job of adding complexity to the portrayal of Jews in Germany. Through characters of Russian Jews, Polish Jews, and Israelis, it situates the current Jewish community in Germany within a transnational and intergenerational crossroads in an authentic manner. However, it still shies away from discussing Jewish criminality directly.

What explains German society’s ongoing silence around the ganefs? Maybe it comes down to fear from the surviving ganefs, or perhaps worries of the pandora’s box seemingly waiting to burst open when discussing Jewish criminality in a still-antisemitic Germany.

David Hadda, the German-Jewish creator of the new mini-series, talks in recent interviews about his fascination with the Jews who got rich through the sex industry in Frankfurt; he calls it an empowering story. Yet much like previous works, the series only alludes briefly and occasionally to the sex industry, without presenting it onscreen. In a way, this coyness continues to replicate the silence around the topic, much like when the words “Jewish mafia” are uttered explicitly in the series — not as a historical description, but only as an accusation the family has to combat.

I would suggest that this silence is rooted in broader stories about Jewish life in Germany. The common historical narrative, promoted by Jewish and German actors alike, has Jews living “auf gepackten Koffern” — on packed suitcases. According to this account, Jews in post-Holocaust Germany treated it as no more than a waiting room, passively accepting local rules while preparing to migrate. This narrative suggests that the Jews who lived here before the coming of post-Soviet Kontingenzflüchtlinge (quota refugees) did so mostly because they were too old, weak, or sick to leave.

But the Jews of the Bahnhofsviertel refute that perception — and this is where talking about them gets troublesome. Far from passive and obedient, they were a group of Holocaust survivors who chose to stay in the cursed land of the Nazis, and they made their living using crime and sex. A few of them even gained enormous wealth. Many sources attest to their enduring hatred for the Germans, which suggests that the ganefs were also motivated by revenge: Whether consciously or subconsciously, concentration camp survivors ripping off ex-Nazis right after the war and profiting from the sex work of gentile women definitely sounds like some sort of vengeance.

What explains German society’s ongoing silence around the ganefs? Maybe it comes down to fear from the surviving ganefs, or perhaps worries of the pandora’s box seemingly waiting to burst open when discussing Jewish criminality in a still-antisemitic Germany.

But perhaps the experiences of the ganefs were forgotten simply because they don’t fit the narrative: The black market avengers’ escapades demonstrate an agency and self-reliance not usually afforded to Jews in post-War Germany. Skilled survivors with Yiddish accents who prospered in Germany without obeying the laws match neither the German image of the passive Jewish victim, nor the Zionist image of Israel as the sole refuge after the Holocaust. Better not to speak of such things.