Facing Ourselves

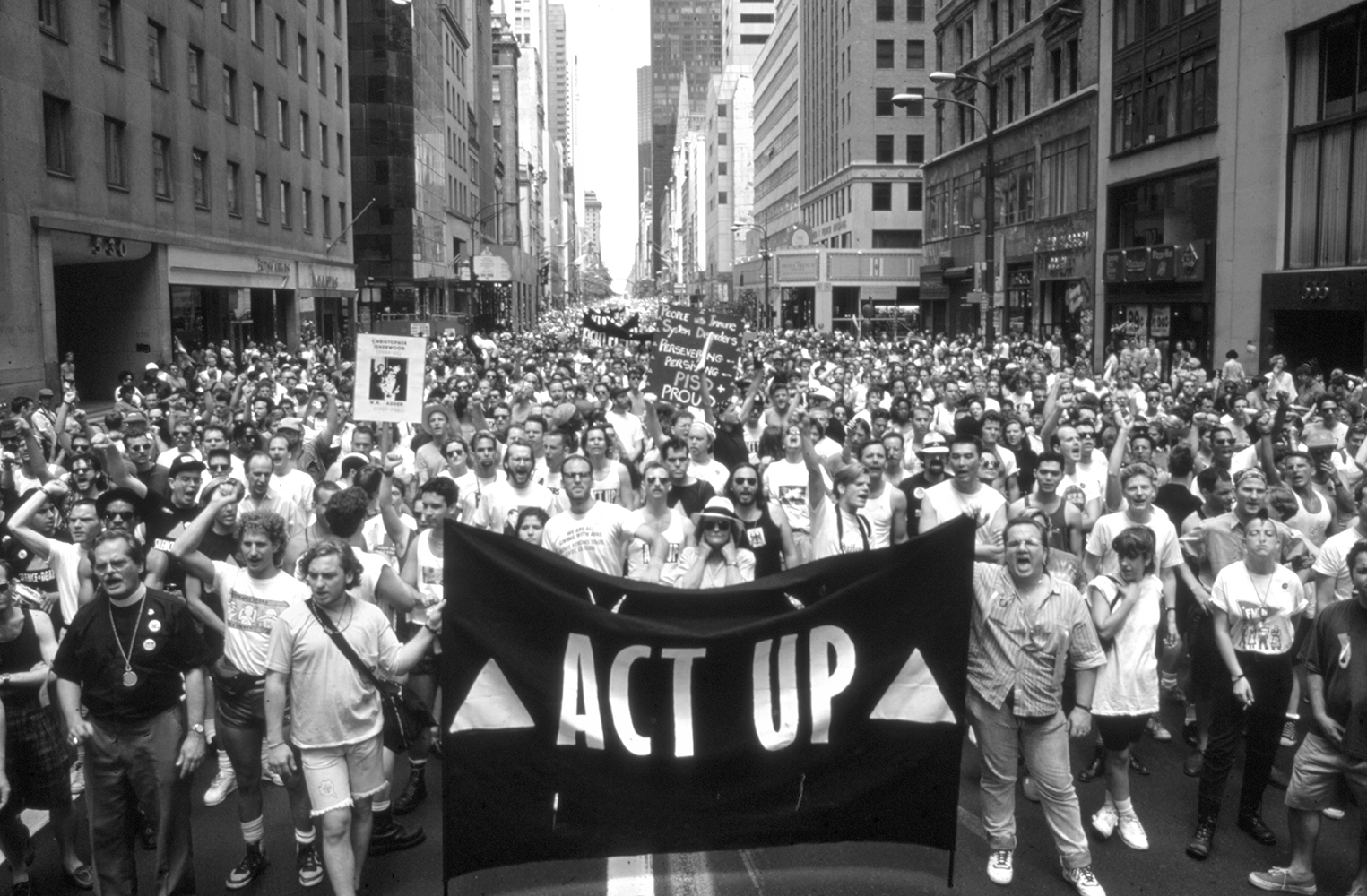

Between 1987 and 1993, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, was the most important grassroots social movement in the United States. Disobedient, unruly, and confrontational, its members were not satisfied merely to “raise awareness.” ACT UP’s activists designed a fast-track system to help people with HIV and AIDS access experimental drugs not approved by the Food and Drug Administration and then agitated successfully for its adoption. Others ran a successful campaign to demand that the Centers for Disease Control change its definition of AIDS to permit women to access medical benefits and drug trials. ACT UP made needle exchange legal in New York City, pressured pharmaceutical companies and the government to change priorities in medical research, and fought insurance exclusions for people with AIDS. And the group raised awareness of the AIDS crisis, through direct actions – shutting down Grand Central Station, interrupting a Catholic mass, storming the FDA, staging die-ins on Wall Street – that disrupted “business as usual” for thousands of Americans. AIDS remains an American as well as a global health crisis, but ACT UP’s success, including pushing government agencies to expand experimental drug access, helped to save innumerable lives. Last year, nearly 31 million people received antiretroviral therapy.

The writer Sarah Schulman has documented the history of ACT UP as both participant and witness. She started writing about AIDS as a journalist in the early 1980s and later joined the movement, attending meetings and participating in actions designed, as another member. Starting in 2001, Schulman began to conduct long-form interviews with 188 surviving members of ACT UP New York as part of the ACT UP Oral History Project, which she co-founded alongside the filmmaker Jim Hubbard. These interviews form the basis of their documentary film United in Anger and Schulman’s book Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993.

At least nine of Schulman’s books take AIDS as a primary subject, but she has also written lesbian thrillers and Balzacian social novels, as well as nonfiction books about familial homophobia and conflict resolution. As an activist, Schulman became involved in the Palestine solidarity movement in the 2000s. Her memoir Israel/Palestine and the Queer International describes the education of a diasporic New York Jew, charting her slow disillusionment with Zionist pieties. Schulman’s writing on Palestine converged with her commitment to gay and lesbian liberation. In a 2011 New York Times op-ed, she criticized Israeli pinkwashing – the government’s use of signifiers of tolerant Israeli gay life to cover up human-rights abuses – and her book Conflict Is Not Abuse, drafted during Israel’s 2014 assault on Gaza, prefigures many of the conversations that have dominated discussions of the current war: the dehumanizing language of corporate media, the pro-Israel bias of liberal institutions like the New York Times, and the footage of atrocities now directly available on Twitter and Facebook.

The writer of more than twenty books, including 11 novels, and many plays and screenplays, Schulman is a significant witness to the defining social movements of the last 40 years. Her writing achieves a rare quality of moral authority, rare because it derives not from declared expertise but from her straightforward firsthand reckoning with the limitations of any single account against the forces of falsehood and oblivion. Taken as a whole, her work is an unsentimental assessment of these limits, the meagre fruits of any single human effort. Yet the world will not change without it.

In April 2024, I spoke with Schulman at two public events in Berlin. The first was a discussion of Let the Record Show at the independent literary venue Lettrétage. The second was a film screening of United in Anger: A History of ACT UP followed by a discussion at Oyoun, a decolonial, queer, and feminist cultural venue. This interview is adapted from those discussions.

– Ben Mauk

Ben Mauk: Why do you think people join movements like ACT UP?

Sarah Schulman: When I started interviewing people, my biggest question was, “What do these people have in common?” I had all these weird ideas like, maybe they had grown up with some sense of community. So in the early interviews I’m asking, “Did your parents belong to the PTA? Did you go to church?”

And nothing panned out. As the years passed, I began to realize that what united these people is that they were the kinds of person who could not be a bystander. And that was it. Aside from that, they had almost nothing in common.

“As the years passed, I began to realize that what united these people is that they were the kinds of person who could not be a bystander.”

BM: It’s impossible to watch United in Anger and not make connections between the ACT UP movement and the contemporary Palestine solidarity movement. ACT UP concerned a population you describe as “a despised group of people, with no rights … [who] joined together and forced our country to change against its will.” The resonance with German attitudes toward Palestinian lives seems clear.

SS: I’m not going to make any comments about Germany, because I am not an expert. But I will say that, whether the cause is the AIDS crisis or Palestine, things only change by coalition.

Most of the people in this world are against this war. It’s the people on top who are keeping it going. It is absolutely impossible to do anything that isn’t in coalition.

ACT UP was not a consensus-based movement. People did not have to agree in order to go forward. ACT UP had a one-line statement of unity: “Direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” Basically, if you had an idea that was direct action to end the AIDS crisis, you could do it.

We would argue. People might yell and scream at each other. But in the end, if you had an idea and I thought it was terrible, I wouldn’t try to stop you. I just wouldn’t do it. Instead, I would go get my five people to do my idea. This kind of radical democracy structure allows a movement to have lots of different actions coming from lots of different constituencies all happening at the same time. And that’s what creates the paradigm shift.

Movements that try to force everyone to think the same, have the same analysis, and agree on one strategy have all failed. Big-tent politics is both our greatest strength and the most important lesson to learn from ACT UP.

“You need an informed movement because you have to design the solution yourself. If you depend on the powers-that-be to solve a problem, and you take an infantilized role, they are never going to fix it.”

BM: Something United in Anger makes clear is how open to conflict the activists in ACT UP were. Not only conflict in terms of internal disagreement on strategy, but bringing conflict into the streets and rejecting likability politics. Was this an explicit strategy?

SS: It was never made explicit. ACT UP was a movement organized around people who had a terminal illness. They had to be effective: they were fighting against the clock.

One of the ways that ACT UP members became so effective was to become experts on their issues. All these people knew what they’re talking about. I interviewed 188 of them over 18 years. Everyone learned about the medication. Everyone knew why we were having the demo. Everybody knew what the demand was. You need an informed movement because you have to design the solution yourself. If you depend on the powers-that-be to solve a problem, and you take an infantilized role, they are never going to fix it.

They don’t want to fix it. They don’t know how to fix it.

So for example, a playwright, Jim Eigo, studied a government agency and figured out how people with AIDS could get experimental medications. It worked. You present your reasonable, winnable, and doable solution to the powers-that-be, they say no because that’s what they do, and then you do the theatrical, creative, nonviolent acts of civil disobedience that communicate with the public through media attention. You use the media to convey that you have the solution to this problem.

BM: You write in Gentrification of the Mind and Let the Record Show about how, in the early 2000s, you realized these lessons were being lost. One of the impulses for the oral history project was rescuing ACT UP’s institutional memory, including strategies that worked or didn’t work, from the mainstream AIDS history. You felt important lessons were disappearing. Is that right?

SS: One of the mistakes people make on the left is to try something that doesn’t work and then do it again and again and again. If it doesn’t work, don’t do it. I know that sounds really simple, but it’s a hard lesson to learn.

One thing that we learned doesn’t work is spending a lot of time on one event. You get all these people to some kind of rally, usually they’re standing in the rain and listening to speakers talk at them. And then they go home. That does not work. That is a waste of time.

What you want to do is build a campaign. You have your demand, and every action you do is to push your demand forward, so that each action leads to the next step. You have to come up with something new. Civil disobedience has to be creative, that’s where artists – I know Berlin’s got a lot of them – come in. Every time you do it, it has to look different. Then no one is wasting their energy. Because it’s very easy to dissipate the energy of your movement.

BM: In the film, we see ACT UP activists occupy Grand Central Station. This is also an action that was conducted [last fall] for the Free Palestine Movement that was organized by Jewish Voice of Peace and If Not Now. There was also a similar occupation of activists this year at the Berlin Hauptbahnhof. Writers Against the War in Gaza have created a newspaper called the New York Crimes, which is something ACT UP did.

So there are resonances between the strategies of direct action practiced by these two movements? Can you talk about the influence ACT UP has had on the Palestine solidarity movement?

SS: The original action at Grand Central was against the Gulf War. The slogan when they took over was: “Fight AIDS, not Arabs.” This has been part of ACT UP’s politics for decades. People are reading the history of ACT UP and using it as a playbook for organization in the Palestine Solidarity movement today. The connections are visible. We’re still taking on the New York Times today, just like ACT UP did, because they are still a tool of misinformation.

For the last 30 years, Palestine solidarity has been a marginalized movement. These organizations like Students for Justice in Palestine or Jewish Voice for Peace are 30 years old. People were writing books that nobody was reading, including me. And ideas were being conceptualized, even though they weren’t popularized. But when it was needed, all this work turned out to be infrastructure. Everything now is happening on top of that infrastructure.

“We have to face ourselves in order to be effective. It’s not pleasant, it’s not comfortable, but it’s necessary.”

BM: It’s very powerful to hear this line in the film that “people with AIDS are the experts on what they need.” That is a kind of energy that I think activists in Germany are struggling to bring to German cultural elites and media institutions here, that they should be talking to Palestinians about what’s happening in Palestine.

Personally, when a German tries to tell me what antisemitism is, as a Jew, I get very angry. German media will tar the most anodyne expressions of Palestinian solidarity as antisemitic. The nonviolent Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement is of course viewed as antisemitic. And the idea that maybe the fact that other people actually have the expertise to tell you what is antisemitic, what is a genocide, what is happening in Palestine – this notion is actively suppressed. You have to claim that expertise for yourself as an activist.

SS: This fake antisemitism thing, it is such bullshit. It is crap. Never again is for everyone. That’s the idea. If whatever people are doing is not “never again for everyone,” it’s bullshit. We have to be strong and resist. This fight about rhetoric goes on every day, but more and more people are on the right side. We just have to keep going.

We all understand striking. We all understand boycotts. But when it comes to Palestine, we don’t understand it because Palestinians have been dehumanized in the public sphere. BDS is the nonviolent Palestinian strategy since 2005. It is the same strategy that was used against apartheid in South Africa. I strongly encourage all of you – I know you’re not supposed to say this in Germany – to support BDS. If we all supported BDS, we would have more power.

I am embarrassed and ashamed that it took me until 2009 to face the occupation. Before then, I basically ignored it. Finally, I made the decision to do the work to understand what was going on, and started the lifelong process that I’m still in the middle of: dismantling the ideologies of Jewish supremacy that I was raised with, not using demography as a form of allyship, and really believing that never again is for everyone. Entering that realm of doubt, of self-criticism, means looking back on your own life, on your family, and realizing that things that you believed and did were wrong. We have to do it, because 30,0001 people have been brutally murdered with U.S. money in our names as Americans and Jews and whoever else identifies with that condition. We have to face ourselves in order to be effective. It’s not pleasant, it’s not comfortable, but it’s necessary.

Sarah Schulman is the author of more than twenty works of fiction, nonfiction, and theater. She holds an endowed chair in creative writing at Northwestern University. A longtime activist for queer rights and female empowerment, she serves on the advisory board of Jewish Voice for Peace.

- At the time of publication, the Palestinian death toll stands at over 46,000 ↩︎